Art Must Go On with Chong Lii and Christian Kingo

As they go through corridors, trains and doorways within a circular motion, the characters in the film ‘Blue Trapezium’ echo the seemingly endless days many of us got stuck in during the COVID-19 lock down. It was certainly so for filmmakers Chong Lii and Christian Kingo whose work is part of SAM’s ongoing ‘Time Passes’ exhibition.

The duo recount how they spent time re-editing the film across cities – Chong is based in Singapore, while Christian lives in Copenhagen – and also continued developing their practices with a little more care and consideration.

Blue Trapezium (2020) at the Time Passes exhibition.

How have you passed time during the pandemic?

CHONG: Giving space to all the loose ends in my life, i.e. stewing on them and feeling paralysed. My day job takes up most of my time. Any time left is usually reserved for other projects (a reality-television inspired series called “Live Creatives Show” is one to look out for) and napping.

CHRISTIAN: During the lockdown, I have mainly focused on research and pushed aside direct involvement in projects. As it has been a time of global isolation, a sort of cocooning state, I’ve felt a necessity to synchronise with that immobile, premature state of dwelling. As an effect of lacking dialogue, the sensation of ‘thinking alone’ has therefore been dominant, which has pushed my thoughts into a less settled territory. I’ve grown an interest in radical ideas on reshaping our world, which has also led me into subjects such as the circular economy, animism and rebirth.

Having to spend long periods at home, has the idea of time changed in any way for you?

CHONG: The earth is a giant. I want to believe that many of us reject and/or at least resent time structures that we’re bound to. I’m sure I do. It is important to remember that our work calendars need to be wrestled with frequently if we’re to have some necessary illusion of balance.

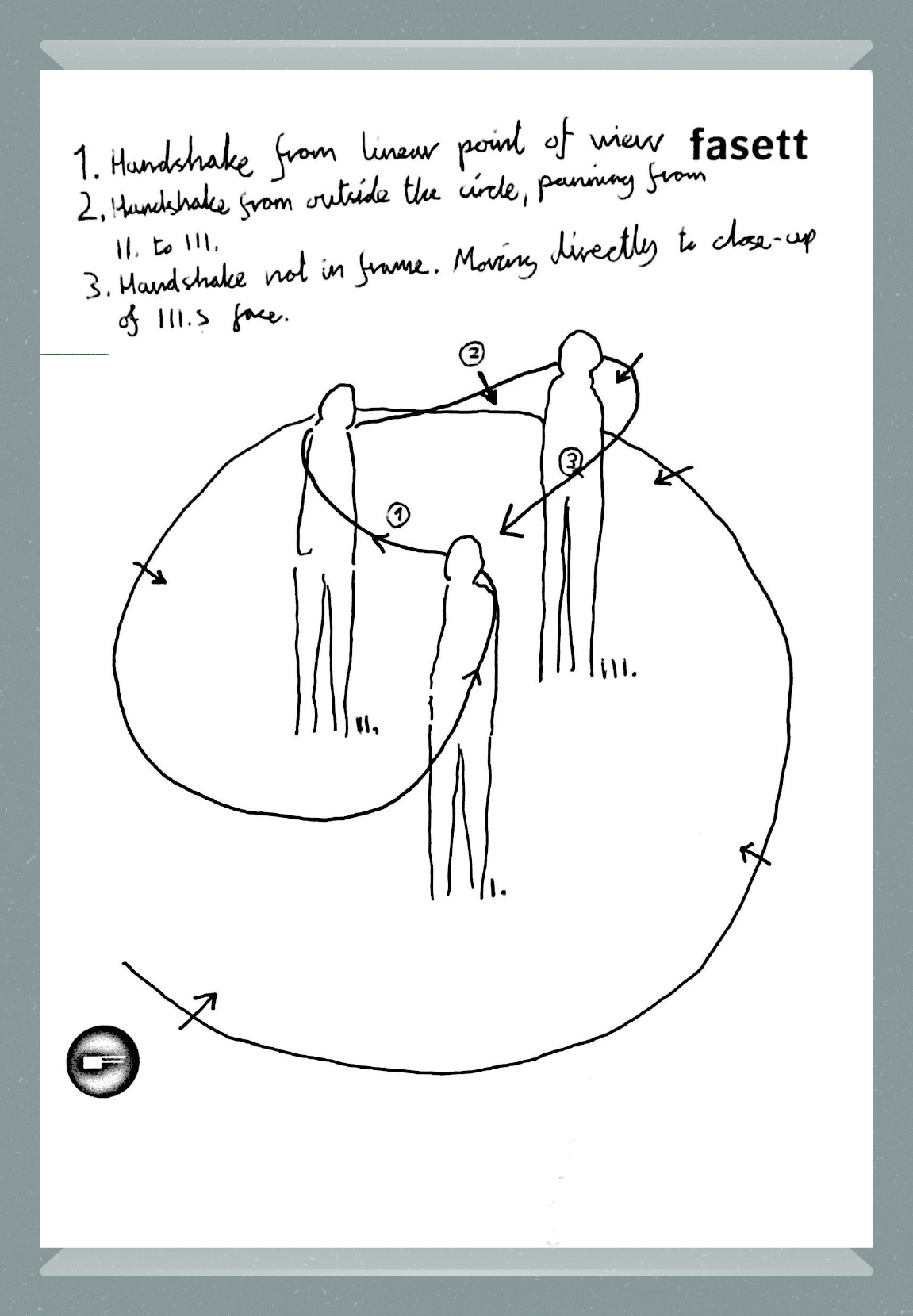

Here’s an illustration of how we planned to shoot a particular scene of Blue Trapezium in one take. I find it oddly fitting in that it reminds me of how seamlessness is usually taken to be a virtue, but take what you will:

An illustration on how the artists planned to shoot a scene in a single take for the film. Image courtesy of Chong Lii

CHRISTIAN: Funnily enough, it seems time moves faster when no longer grounded in a schedule, days or a potential end to its current state. It appears that when time isn’t being asserted any significance, it simply just floats, much like natural phenomena, i.e. oceans, magnetic fields or winds. I won’t say that my idea of human time has radically changed, but I have definitely been speculating on correlated time-frames, such as ours in relation to the giant we live on.

Has the pandemic impacted your views about art? How might we see it in your work for Time Passes?

CHONG: The work itself was conceived and finished in 2017 – there was no reckoning with a pandemic to be had. When Samantha (guest curator for Time Passes) got in touch and expressed an interest in showing it, we took this as an opportunity to revisit and reconsider the nature of the piece itself. Communicating virtually between Denmark and Singapore was something we had already gotten used to doing before this. Reconstructing the material offered some masochistic pleasures – a reason, not an excuse, to focus on romanticising 2017 instead of staying put in 2020. Perhaps for those of us who are lucky enough to have a sustainable routine at our homes this year, our glutton-for-punishment tendencies have become more pronounced. This sense of masochism might be intuited when one is viewing Blue Trapezium.

CHRISTIAN: In our re-edit of Blue Trapezium, I felt the work has become more relevant in its portrayal of individuals drifting through deserted public space. As we have all probably experienced during the pandemic, public space potentially seemed at one point like a relic of the past. In this regard, we did choose to put much more emphasis on the conflict between individual and environment. By removing the initial film score and really pushing the environmental soundscapes around our characters, their relations became much more representative of abandoned cities, transforming into liminal spaces.

Behind the scenes of shooting a torture scene in the film. Image courtesy of Chong Lii

The possibilities of caring and continuing are major themes explored in this exhibition. How might they relate to your practice?

CHONG: I’m usually interested in exploring how disparate and combustible notions/things can be merged in a linear framework. So naturally, dimensions of care and empathy need to be considered, negotiated and maintained at very early stages, especially when a camera and some idea of collaborative performance is involved. I remember that we wrote these characters as semi-neutered individuals who were hazy with manifesting “civilised” structures of kinship and social engagement – even the act of gathering and sharing space would feel like a threat. Their collective hypnosis suspends them, closing the possibility of outright conflict, but also disabling any modes of connection.

CHRISTIAN: I feel the act of continuing has taken a different form, where you actively have to consider what to either rebuild or reshape. In my own practice, I definitely feel this reshaping in creating narratives that question both conservatism and the already progressive movements. I think the acts of caring within my practice emerges, by the same question, as an interrogation fluctuating between different opinions, creating a sense of diversity in its overall view.

Behind the scenes of shooting the film in a location using only blue light. Image courtesy of Chong Lii

In such challenging times, what are some ways you have taken care of yourself, your practice and others around you? What role can art play in all of this?

CHONG: For me, it’s about getting better at admitting that I don’t always take care of myself very well. Being accountable to yourself and others about this is probably a very basic mode of responsibility that one should hope to have – it’s obviously easier/harder for different people but it can be crucial. The idea is to eventually go beyond just accepting it and hopefully addressing the nuances of your own experience (probably best not done alone).

I don’t think art should necessarily always be expected to play a role in “advancing” something as precious as care. Feeling beholden to catch-all expectations of art bearing such burdens, so to speak, can easily lead to wilder, aggressive forms of vanity and entitlement between viewers and artists. I find that be an unfortunate by-product that can end up dwarfing any good intentions or challenging conversations. Not everything fits in a problem/solution matrix.

CHRISTIAN: Films have had, as always, a very nurturing role in both my personal life and practice. These two aren’t really separated anyhow. During the pandemic I have dived into dystopian anime, as it seemed watching human behaviour through animated distance by imitations, have had an effect similar to healing. Also, the films of Tsai Ming-liang have been truly healing for me during the pandemic. His subtle interplay of individuals and environments has been very fitting for the loneliness of recent times. In social relation, the main format has been long walks through empty cities with good friends. I think in times of despair, reaching out to people you care for is the most important, especially family. In my case, emerging from the pandemic has even fuelled numerous reconnections.

A makeshift standing desk setup that Chong Lii created back in 2017 for editing the film, because “haemorrhoids aren’t worth it”, he says. Image courtesy of Chong Lii

A makeshift standing desk setup that Chong Lii created back in 2017 for editing the film, because “haemorrhoids aren’t worth it”, he says. Image courtesy of Chong Lii

‘

Time Passes’ is part of ‘Proposals for Novel Ways of Being’, a collective response by the visual arts community to the global pandemic and its impact on our community. Come see the work of Chong and Christian along with 11 other artists at the National Gallery Singapore from now till 21 February 2021. For more information on 'Time Passes', please visit https://bit.ly/sam-timepasses.