Deep Cities Diving with Finbarr Fallon

Singapore’s urban development can be seen today in its skyscrapers and extensive land reclamation. But what happens when space runs out in the land-scarce city? In his artwork for SAM’s hoarding commission series, Sub/merged, artist Finbarr Fallon speculates on the next frontier: underground living. He takes us deep into his fascination with what lies beneath cities, the stream that used to run below SAM and the hidden potential of subterranean cities.

Sub/merged is your second work about underground cities after the animated film Subterranean Singapore 2065. How did you first get interested in subterranean cities?

I have always been interested in subterranean spaces, and list caving and urban exploration as two passions of mine. Having experienced these underground landscapes, I find it a pity that when one thinks of being underground in the city, what commonly comes to mind is only quotidian or utilitarian landscapes such as underpasses, service tunnels, areas housing transport infrastructure.

The underground is more than a teeming mass of transitory spaces; it has also played a key role in the development of human imaginaries, ranging from the sacred to the technological sublime. As cities become increasingly built up, quite literally, and surface conditions become increasingly uncertain, I began to wonder how the underground would feature in future urban imaginaries, and how it could present a speculative environment for urban verticality and liveability.

The underground is more than a teeming mass of transitory spaces; it has also played a key role in the development of human imaginaries, ranging from the sacred to the technological sublime.

Finbarr’s interest in the subterranean has led him to explore underground spaces around the world including Hong Kong’s Shek Pik Reservoir (Courtesy of Finbarr Fallon).

In what ways does Sub/merged build upon and/or depart from ideas you first explored in your earlier work?

Sub/merged similarly builds upon the idea that living underground is a plausible and even desirable urban future. But unlike Subterranean Singapore 2065, it is focused on normalising living underground, by presenting a slice of everyday life in a subterranean context. The inclusion of activities and landmarks that are familiar to visitors to the Bras Basah.Bugis precinct, such as commuting and the library, will hopefully subconsciously resonate with viewers to generate a sense of optimism and excitement about a subterranean urban future. This is in contrast to the cautionary tale told by the Subterranean Singapore 2065 narrative, which developed a vision of the underground as a spectacular showcase project that could be enjoyed only by select social groups.

The film Subterranean Singapore 2065 looks at how large-scale underground living could happen in Singapore when it turns 100 and was created in 2017 while Fallon was studying for his Masters in Architecture at The Bartlett School of Architecture in London (Courtesy of Finbarr Fallon).

While printed on a hoarding, Sub/merged contains various animated visuals. Tell us more about the analogue and digital methods you used to make this work come “alive” for the viewer.

The use of augmented reality was key to this – it lets passers-by momentarily enter into the diverse worlds depicted on the hoarding, and record their experience through the use of real-time 3D Instagram and Facebook filters.

This is also supplemented by a website. which animates the scenes depicted on the hoarding artwork with the ebb and flow of daily life – people and machinery in motion. The website enables the hoarding to ‘come alive’ even for those who can’t experience it in person. This was something especially important to me as it enabled my parents, unable to travel to Singapore because of COVID-19, to experience the artwork in a mediated form.

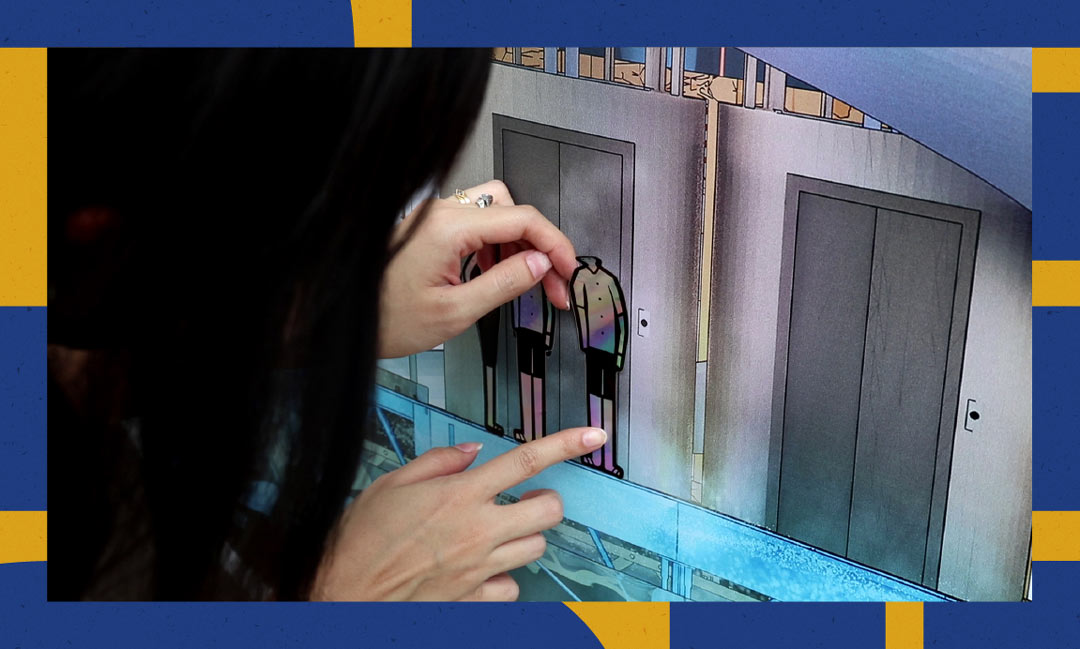

The underground city on the hoarding is also populated by thousands of humanoid figures in the form of holographic stickers. The intention was for these to shimmer and flicker as light passed over them to enliven the hoarding. Be it sunlight dappling through the trees overhead, or the passing of cars driving along the adjacent road in the evening, the brief illumination would make it look like the figures were in constant motion across the hoarding.

Sub/merged features holographic stickers of figures that shimmer and flicker when light is passed over them, as if in constant motion (Courtesy of Finbarr Fallon).

Sub/merged responds to the site of SAM. What are some lesser known histories about the area or its underground that informed the work?

Something I really wanted to pay homage to was the origins of the Stamford Canal. This was a small freshwater stream called Sungei Brass Bassa, but has now become a covered concrete culvert buried beneath the streets of Bras Basah. In fact, if you are walking along Stamford Road, you can peer through the steel grilles to see the water below.

In my work, I wanted to build on that narrative of bringing freshwater underground, by envisioning underground reservoirs that transcend its utilitarian function. So one possibility I explored in the work was making these reservoirs readily accessible as sites of recreation and modes of transportation – as public leisure gardens, but also avenues for floating transportation.

In your imagination of the underground, nature in the form of landscaping and agriculture is prevalent. Why is this so?

A key challenge to making subterranean environments liveable is the difficulty of bringing in natural elements within the space. This is important to create a sense of psychological comfort and wellbeing, especially for extended durations of inhabitation.

In Singapore, in particular, the role that greenery has played in creating a strong sense of place in modern-day Singapore is incontrovertible. Hence, it seemed natural to infuse greenery throughout an iteration of an urban underground in Singapore – albeit in a whimsical way inspired by technologies which can sustain life deep underground, such as solar reflectors and suspended aeroponic systems.

Moreover, as Singapore accelerates its food resilience efforts, there is a ramping up of local high-intensity, high-rise farming to raise production. Unlike the “traditional” land-based farming, this farming takes place in highly controlled environments. Hence, I propose to site these uses underground on a large scale, to free up more space for surface uses.

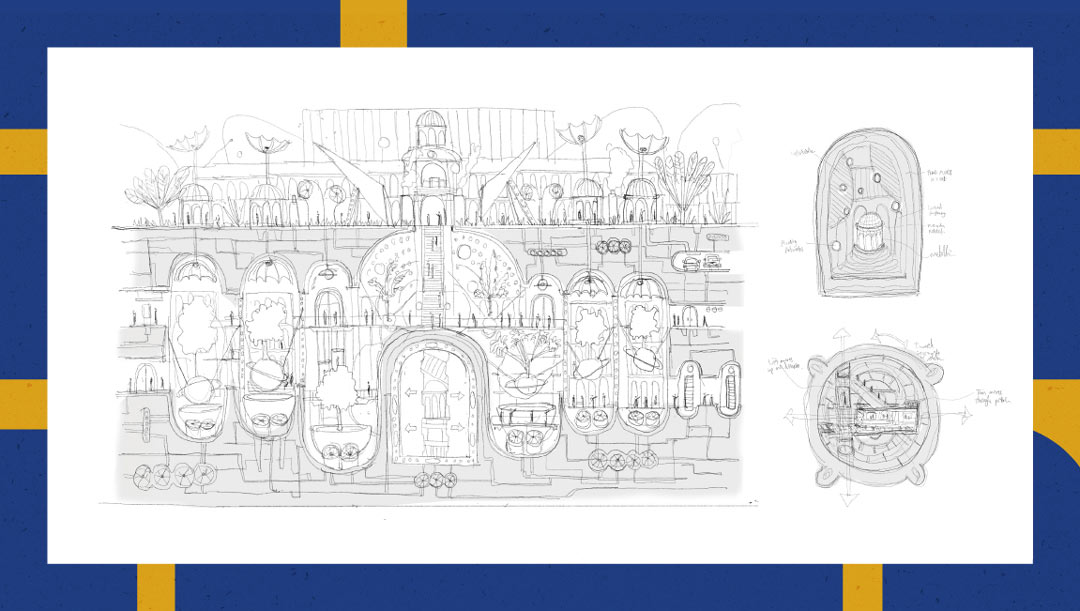

An early sketch of Sub/merged (Courtesy of Finbarr Fallon).

You are trained in architecture and also an architectural photographer. How do you think subterranean cities will change the way we view buildings and design them?

Buildings in the first instance were conceived as shelters from the outside environment. But moving underground could take this to the extreme, resulting in very limited access to external environmental stimulus like natural light, which are critical to well-being. So for subterranean cities, one key challenge will be how to convincingly re-create “natural” external environments in these highly interior spaces, that can minimise feelings of disorientation and sensory deprivation.

Bras Basah MRT station, strategically located just across from SAM, is a great example of design that has addressed a key issue of making subterranean spaces liveable – the reduced exposure to natural elements, especially natural light. The reflection pool at the Singapore Management University above doubles as a skylight that lets sunlight stream through to reach the second deepest MRT station in Singapore at 35-metres below ground, and enables commuters to feel better-oriented in their surroundings.

The other question, which I don’t have an answer to right now, is how we will be able to move underground on a large-scale while interfacing with surface living, and designing to minimise our environmental impact.

A video showcasing Sub/merged installed around the SAM building along Bras Basah Road (Courtesy of Finbarr Fallon).

While Sub/merged is speculative, Singapore already has many underground facilities and even an underground masterplan. What about subterranean Singapore are you most looking forward to?

As developments like Marina Barrage and Jewel have shown, Singapore has the vision and skill to combine problem-solving engineering feats with compelling place-making to create unique destinations. Even though the government has stated there is no intention for residential use to be located underground as part of this masterplan, I am looking forward to seeing how Singapore will apply these capabilities to develop the underground as a liveable environment. Especially how nature will be integrated into an underground environment as an extension of Singapore’s “City in Nature” vision.

No need to go underground to see Finbarr’s subterranean Singapore. See it installed on the hoarding around SAM’s building on Bras Basah Road until 6 June 2021, or explore the work online at the 'Sub/merged' website. For more information, visit https://www.singaporeartmuseum.sg/art-events/exhibitions/submerged.