What Lies Below SAM

Singapore’s constant upgrading is visible all around us. In SAM’s latest travelling exhibition, The Dream from the Other Side, artist Melissa Tan explores the topography of Woodlands, Jurong and Tampines to create a series of artworks that map their transformation over time.

The ongoing redevelopment of SAM has also given archaeologists and engineers the opportunity to dig deeper into the past of where we stand on. Our heritage buildings reside in one of the city’s oldest districts: Bras Basah. It is home to many historic buildings – including that of the former St. Joseph’s Institution (SJI) and former Catholic High School that make up SAM – that date back to the 19th and 20th century when Singapore was part of a British colony. But the past is visible not only in architecture, they lie in the grounds beneath them too.

Image courtesy of Aaron Kao.

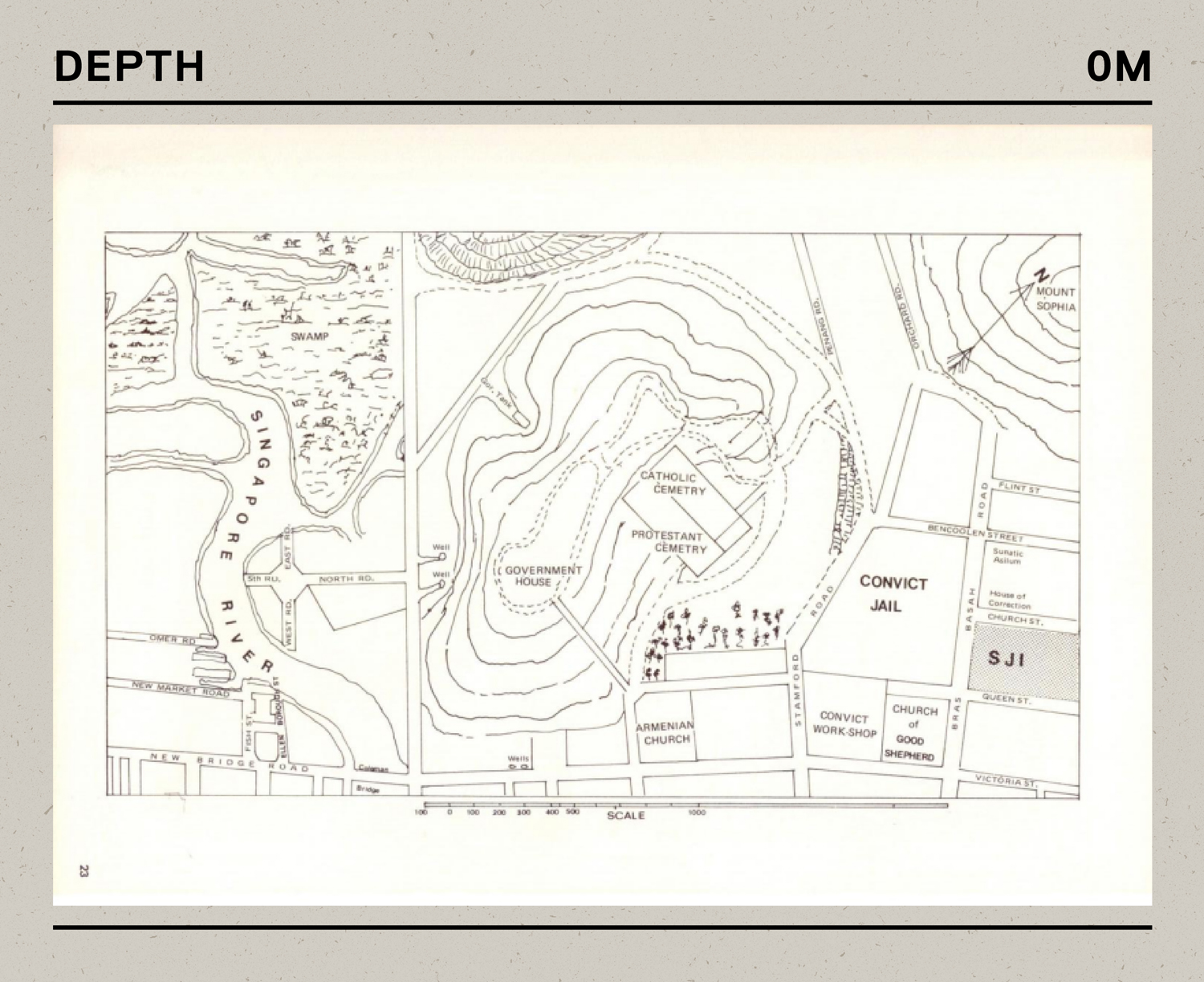

0 m below ground

SAM is not far from Fort Canning, once home to a pre-modern settlement in the 14th century. It is also located across a former jail built by the British in the mid-19th century to house Indian convicts they brought in, as shown in the map below. The Archaeology Unit at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute set out to find clues to these historical periods which are relatively unknown. They also hoped to locate remains of Singapore’s first Roman Catholic chapel, which was erected at the grounds of SAM in 1833 before SJI was built almost two decades later.

Image courtesy of St. Joseph’s Institution.

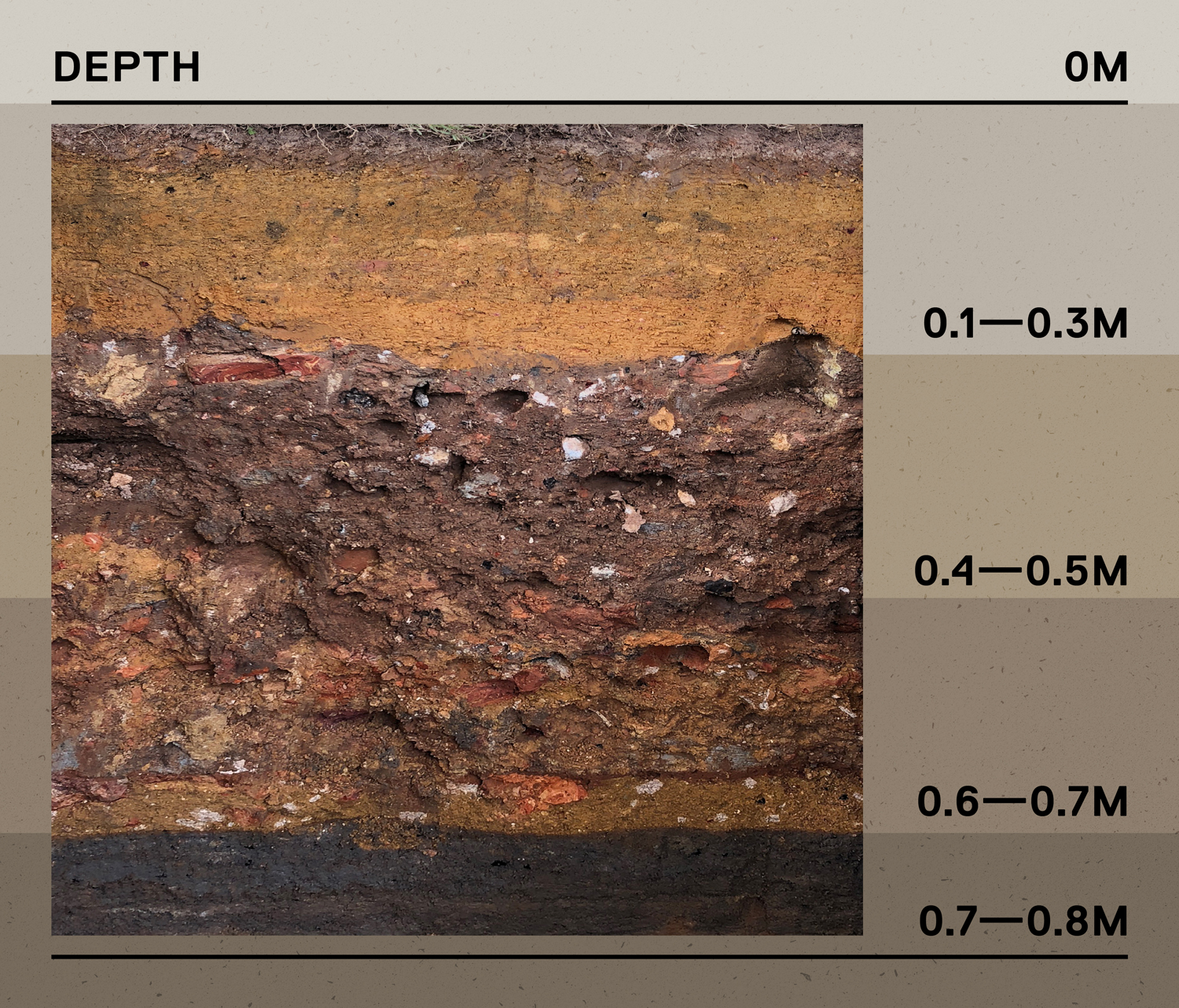

~ 0.1–0.3 m below ground

Over a month in April 2018, the archaeological team excavated nine pits in SAM’s courtyards and front lawn. Each measured between 1-by-1 m2 and 2-by-1 m2. Above is one from the south corner of the front lawn. At this depth, there was a layer of topsoil followed by modern landscaping fill – commonly found underneath buildings in Singapore.

~ 0.4–0.5 m below ground

An abrupt layer of colonial construction debris marks the British arrival to the area. As the mixture appeared to be churned and redeposited, they are possibly by-products from the construction of what was then SJI. The layer did not represent any chronological pattern, and the artefacts unearthed, as shown below, were typical domestic refuse ranging from the 1850s to 2000s.

Selection of ceramics recovered.

Image courtesy of Lim Chen Sian.

Brick fragments and a variety of tiles.

Image courtesy of Lim Chen Sian.

The oldest artefacts discovered were from the mid-19th century, such as this European salt-glazed stoneware ink bottle.

Image courtesy of Lim Chen Sian.

~ 0.6–0.7 m below ground

The orange-brown clay strata is not native to the site. It was probably introduced by the British within a very short time to reclaim the area’s marshy grounds and develop the new town.

~ 0.7–0.8 m below ground

A thin distribution of charcoal in black was observed in the Paleo-river bank layer of the nearby Sungei Bras Basah, which has been built over and turned into Stamford Canal. It was believed that “Bras Basah” is a misspelling of beras basah, which means “wet rice” in Malay.

One of the nine pits excavated by the archaeologists.

Image courtesy of Aaron Kao.

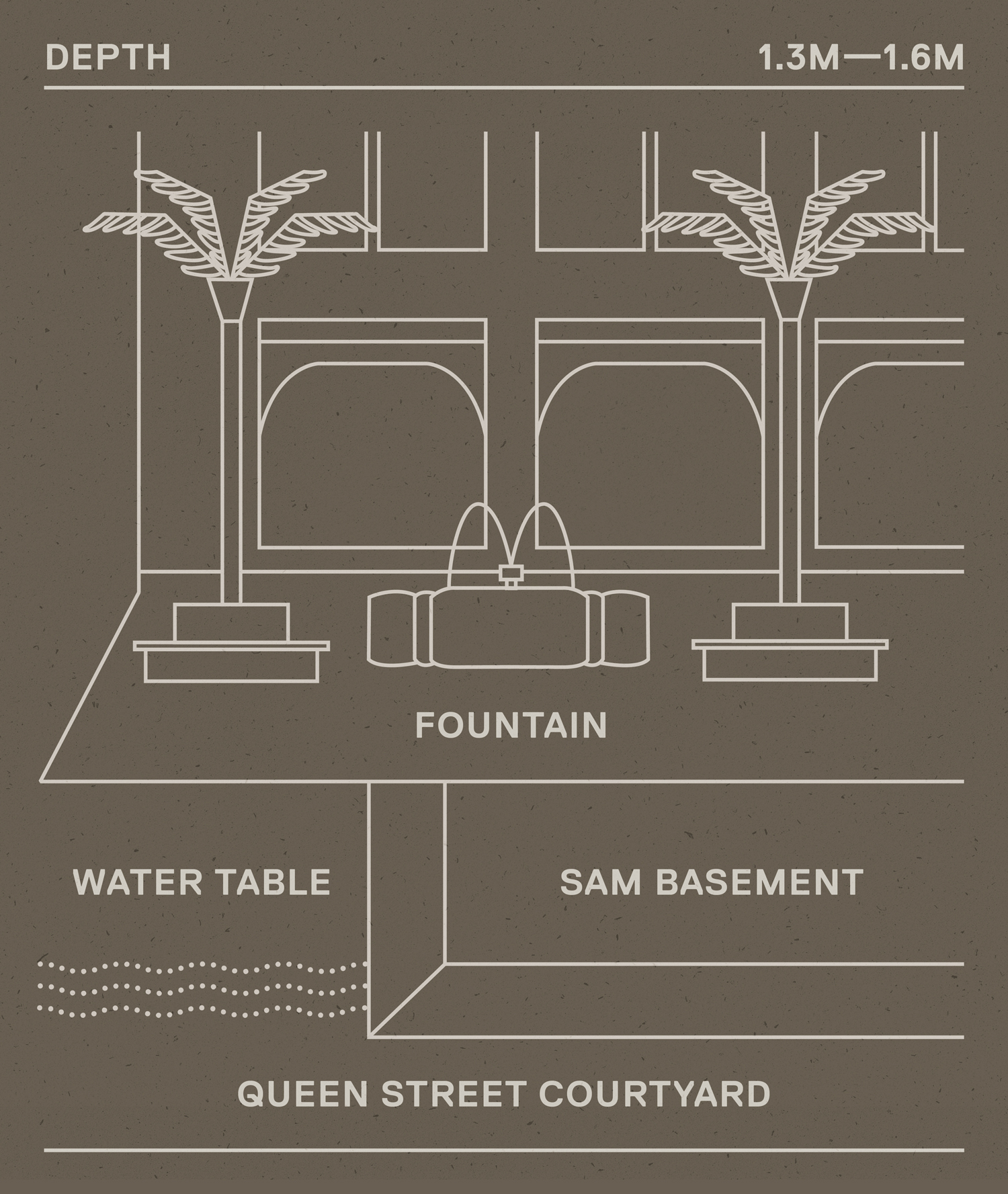

~ 1.3-1.6 m below ground

As part of any major construction works, a soil investigation was also carried out to determine the characteristics of the land. Drilling into the courtyard of SAM, engineers discovered the water table at this depth, where the soil and rocks are permanently saturated with water. As SAM’s basements are easily double the size of this water table, engineers will have to ensure they are properly waterproofed!

~ 29 m below ground

SAM rests on the Kallang Formation, a layer or sediment formed in the late Pleistocene (0.14 million years ago) to today. As seen in the core sample below, it is primarily made of soft marine clay, loose alluvial muddy sand, soft peaty and organic mud – typical of areas around the nearby Singapore River and other coastal lands. The upper layer of this marine clay strata is free of oxygen, which encourages the preservation of organic plant remains. Archaeologists could study them to find clues of past environments, the morphology of ancient landscapes, and how people interacted with their surroundings.

~ 34 m below ground

Another geographical formation below SAM is the Fort Canning Boulder Bed. Formed in the late Cretaceous period (100–65 million years ago), it is characterised by hard, often red and white, unstratified sandy silty clay, and contains many big lens-shaped to rounded fresh sandstone. Just like the core sample shown above. Such a formation is also found across the central business district of Singapore.

Digging to discover more about SAM’s historic past? You can also follow our Facebook and Instagram pages for the latest updates on SAM’s redevelopment, upcoming events, exhibitions and art collection.