Electric Intimacies with bani haykal

01 Sep 2022

bani haykal’s practice has long involved the creation of DIY tools—musical instruments, mechanical keyboards, encryption software and audio samplers, among others. Yet haykal approaches such machines as more than utilitarian contraptions, but also as experiments in new forms of relationships between humans and machines. If technologies like machine learning and artificial intelligence re-create the world in abstract digital terms through data collecting and modelling, haykal suggests that there may be alternative interfaces between living and non-living things that re-cultivate a sense of spirited embodiment. In the discussion that follows, haykal focuses on sifrmu and momok elektrik, the latter being a recent acquisition in the collection of the Singapore Art Museum.

The following conversation is excerpted and edited from a public talk on 5 June 2021.

***

When you first mentioned to me that you were thinking about “encryption” and “intimacy” together, I didn’t get the relationship between the two concepts. In news headlines about technology, encryption suggests protection from security threats—as in, you don’t want a hacker to steal your password, so it’s being encrypted. Encryption is understood as a vigilant act of self-protection. But you’re suggesting that there’s something else about encryption that is core to our relationship with machines, and how we become close to them…

Much of what our thinking about encryption, as you mentioned—yes, a lot of it—is about hiding, or even this idea of cryptographic analysis that deals with uncovering something—but the root of it, for me, has always been about how people have an intuitive sense of encoding, of making something that’s not privy to others. An inside joke, for instance, is something that is shared between two people, and no one else coming into that circle would be privy to what it actually means or what it was actually pointing towards. An inside joke exists only between two people or a select group of people. The way that an experience is encoded between that small group of people, for me, is a form of intimacy. It signifies that there is something that is shared, that these people who share this inside joke share a certain intimacy to a particular moment, or to a particular encounter. End-to-end encryption, for instance, where it’s only between two users, also points towards the question of what it means to contain intimate moments or intimate encounters between bodies.

It felt necessary to think through what it means to have this sense of closeness, or to be intimate with someone through our devices, and also with our devices as well. If you set your keyboard, and depending on the kind of keyboard that you have—it could be a mechanical keyboard or a laptop keyboard – you could have shortcuts that are already set, in order for you to communicate, or to execute certain operations that you want your computer to do. That is unique to just you and your personal computer. It is necessary to think through how we are being intimate with machines and being intimate through machines, when we address what it means to encode the other.

I think you put a nice spin on it, in thinking about it as the intimate, or even private, language between human and machine. That challenges some assumptions associated with discussions around “privacy” today. There’s top-down thinking about legal and regulatory frameworks, and a more bottom-up approach, with obfuscation tools you can install and use to protect yourself. But it seems that the language in either case focusses on individual personhood. It’s about building these walls around yourself, to prevent other people from encroaching. I sense that you’re not so much interested in that individualist notion of protection, but rather about sharing or being in relationship with other things.

Absolutely. I think, admittedly, sifrmu came from a personal place as well, thinking about that first immediate encounter, a relationship that I would have either with people or with computers. But I think it’s scalable, expanding to think about what it means to organise, to collectivise, through very personal languages that are unique to only specific groups or specific people. That’s central to the project: what it means to generate or to develop a kind of language system that is only identifiable and decryptable within a circle.

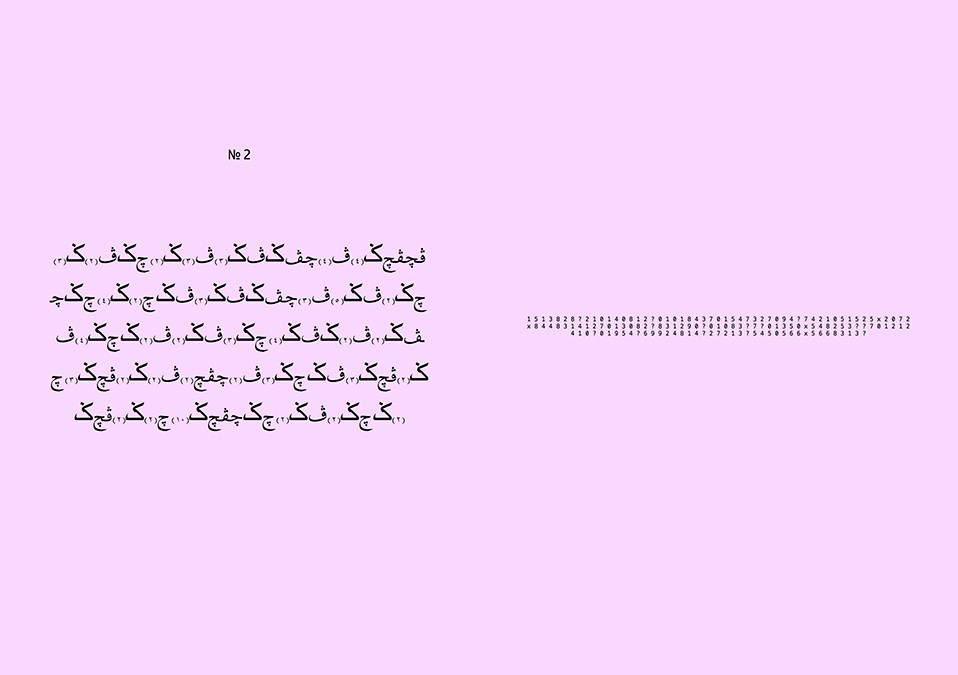

sifrmu started in 2019. On the left side, you see an entry box, a field to enter your text. This is where plain text is typed in, so when you utilise this program, you are interacting with this side of the screen primarily. You type in anything that you want, and then when you hit “enter,” it starts encrypting your text into Jawi characters. You will notice that there’s a repetition of only three Jawi characters, which are “cha,” “gah,” “pah.” These are three of six unique characters within the Jawi script, which Arabic script does not have. In case this wasn’t prefaced before, Jawi was utilised for written Malay at one point in time. If you look through archives, you’ll find many Malay texts written in Jawi.

In the original version of sifrmu, the program encrypts each character into Jawi and a number. Subsequently, it progressed into encrypting Jawi and MIDI values. So, every Jawi character has a unique MIDI value, from which a sonic output is then produced. In this version, the program encrypts into a MIDI value, but the MIDI value does not generate a tone. It triggers a sample from within a library of sounds. So, the sounds are richer and more complex in this particular version. So sifrmu converts plaintext into Jawi ciphertext, which is half of the encrypted information, while the other half exists in sound.

That’s a key part, the sound element of the encryption. When you type something in and hit “enter,” the encryption doesn’t happen immediately. These sound samples are being played sequentially, and then the text also appears sequentially. There’s a sense of rhythm that you have consciously built into the system. You’ve used this algorithm behind it to also perform in live settings as well. Could you speak a bit more about how sound is built into sifrmu, and how that experience of it unfolding over time is important to you?

In my encounters with encryption processes or ciphers in general, they are static in nature. You encounter a ciphertext, and then you eventually have to analyse it, find a way to decrypt it. Whereas, with sifrmu, what I was interested in, was to keep it dynamic. It is still rooted in a static form, in that it’s based on characters or numbers, but the output isn’t necessarily bound to that. When MIDI values were being triggered in the original version, you’re getting synthesised sounds. If you had a transcript of just the Jawi script generated from sifrmu, it is incomplete – you need to match it to the sounds that you hear. I think that the lure of it, for me, was to create something almost impenetrable by other things. Because if I were to create the decryption program of sifrmu, you could play whatever here, and this thing registers that and just goes, “Ding! Okay, so this was the message that’s being sent out.” But if you don’t have that, you need to listen or figure out what this process was.

Even in your comments earlier, you were saying that you are interested less in direct communication than the transformation and poetry that comes out of it. That’s key to thinking about sound as well. There’s a certain kind of classical theory of communication, which concerns itself with sending a message from Point A to Point B. And if there’s noise along the way, that’s bad. Because you want the message to transmit as clean and intact as possible. But this offers a narrow understanding of what is valuable in communication. There’s the other aspect of the aesthetic experience that happens in between.

At least for me, I look at encryption as a creative form of expression. I spoke about someone growing up as a Muslim, but who does not speak Arabic. I grew up needing to recite the Quran, meaning that I had to learn the Arabic script. But there’s a difference between reading the Quran and reciting the Quran – I can recite the Quran, I think I can do a pretty good job at it, but I don’t know what I’m reading! I do not understand the words, the phrases, the poetics of the Arabic language, when I recite the Quran. That, for me, was a really important distinction. I’m not exactly reading and nearly performing a series of sounds. Of course, I could take the effort to know what these words meant. But from a young age, it was just given that you need to learn how to recite properly. That, for me, is musical because I’m just executing accents. I’m just stretching vowels, consonants, so on and so forth. Much like music, it’s interpreting what I encounter and finding a way to make it even more melodic or rhythmic in nature. I think this threads back to thinking about what it means to have creative expression of encoded information.

There’s a sense of meaning, a sense of weight and presence to the recitation. Even if the text itself might not be comprehended, that entire experience is still very meaningful. In considering these sensorial facets of experience, we’ve spoken about the visual and the sonic, but there’s also touch—the way that you interact with the keyboard to type text into sifrmu. You have spoken about the keyboard as almost an extension of ourselves, something that we spend a lot of time with, that is designed to accommodate digits on it all day. How have you approached the relationship between tools and your body? You’ve also constructed different kinds of musical instruments that play with this relationship. But what’s special about the keyboard for you?

Initially, it was just how the keyboard is one of the most intimate keepers of secrets. In the same way that walls could talk, if the keyboard could talk, it would say a lot of things. Sentiments, words and confidential materials pass through it. The keyboard keeps all of that. Actually, if you look at different people with different keyboards, on your laptop or any of your mechanical keyboards, you will notice that different people would have different marks on each key, depending on the frequency of what you type, and who you’re typing with. For mine, the letters “A,” “S,” and “shift” are worn out, for instance. These are interesting signifiers of how we utilise the keyboard.

The other thing that I also wanted to touch on as well, in relation to time, goes back to sifrmu. One of the original ideas for this project was to be able to log the rhythm of you typing—how fast or how slow you type. This would determine the musical output of the audio source. So, it’s not something which is calibrated statically. It’s generated dynamically, based on user input. With a program like Pd (Pure Data), there’s so much that I’m still learning from it, but this desire to always be able to create new instruments has been an important part of my practice. I like the idea that an instrument is a tool, and that you could always create new tools or modify tools to enact specific expressions that you want. Pd and sifrmu were not just a long time coming, but it also required a few years of trying to understand how rich these applications are.

That richness is then built on for a project like momok elektrik, where the sound-generating software takes a physical manifestation as an installation. But what is also important on the back-end is that you’ve given over control of the composition to the software entirely. Could you talk about the decision to shift the agency over? How did you decide for it to become almost autonomous?

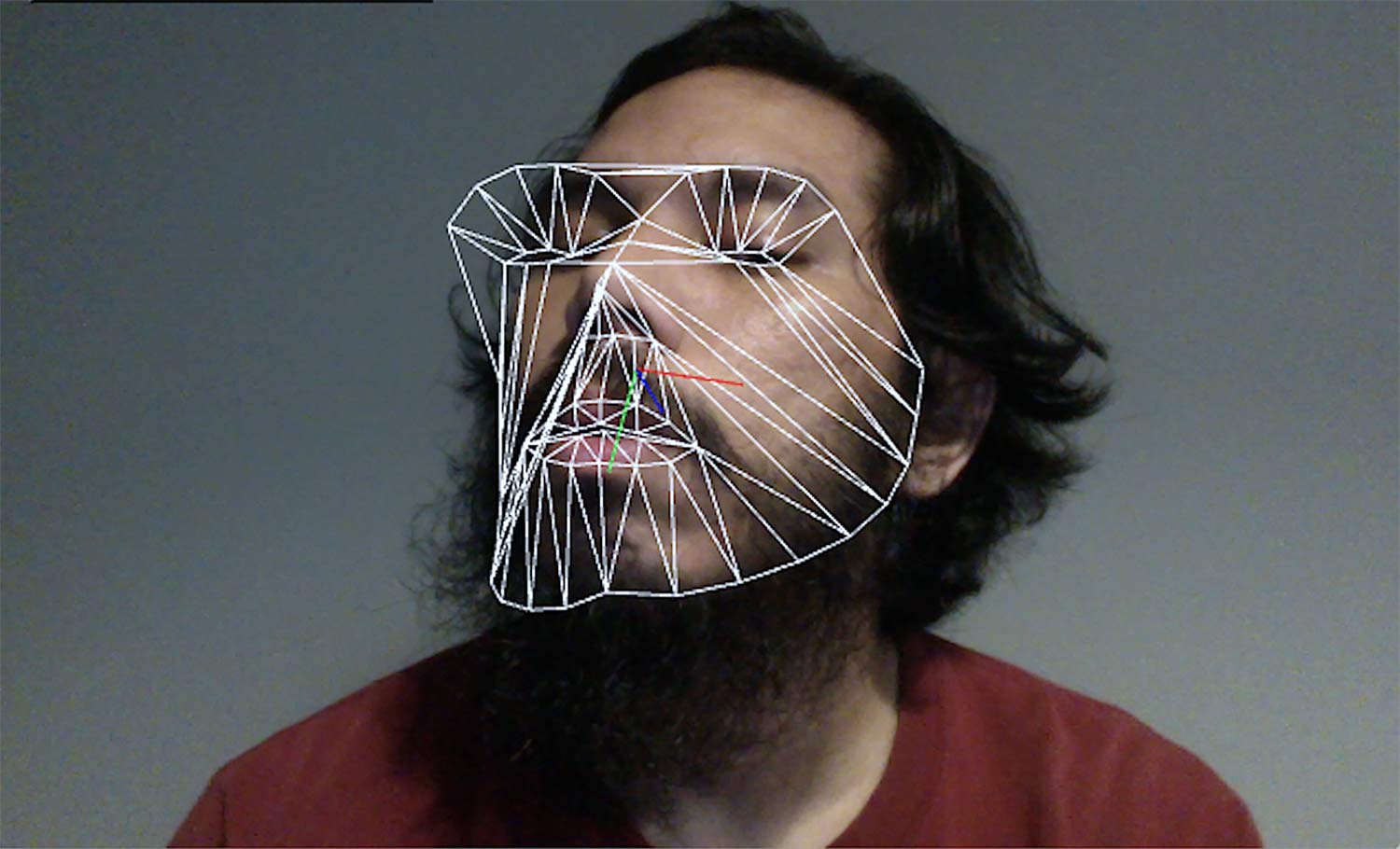

I’m mindful of the encounter of someone listening to momok, like, what is orchestrating this? Did someone just press play, and it runs in a linear fashion? I’ll go back to some of the central features of momok. It’s a nine-channel sampler, with nine outputs that are going out. Each channel is controlled interdependently from one another, so there’s a central BPM (beats per minute) that runs, but each of these channels would go in its own subdivisions. The reason for that also is because I would like to encounter a different kind of rhythm, a different kind of sensibility to how these samples or these voices are arranged. It’s one thing for me to manually compose how these voices appear. But it was also quite interesting to get a machine to churn out these possibilities, because ultimately, it is about the order as to how these samples are performed or triggered. In a piece I collaborated on with Lee Weng Choy, Trouble with Harmony, 80% of the composition was generated by momok as an instrument. The other 20% is me removing some samples, cutting, cleaning, to tidy up the composition. But in the gallery space, or in these spaces where momok exists, I wanted that sense of mystery, as to what the underlying instinct or motivation is for the machine to breathe in a particular way.

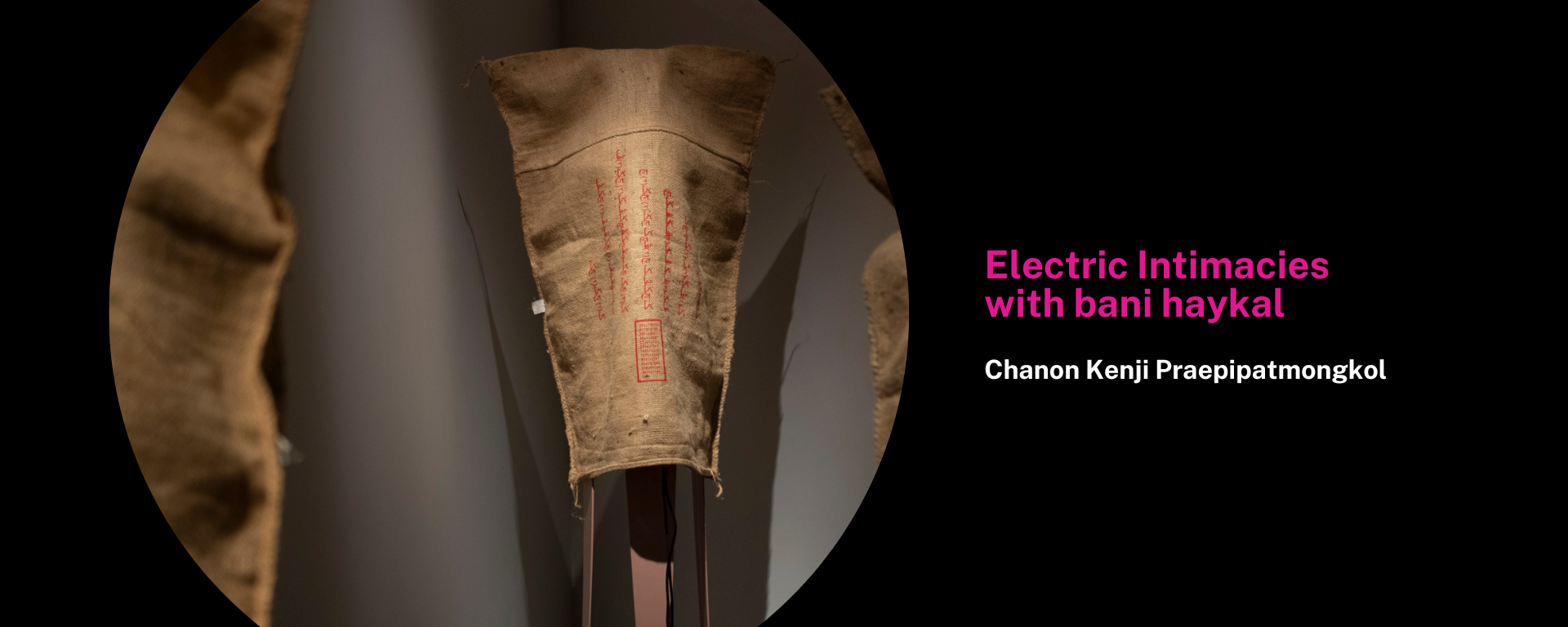

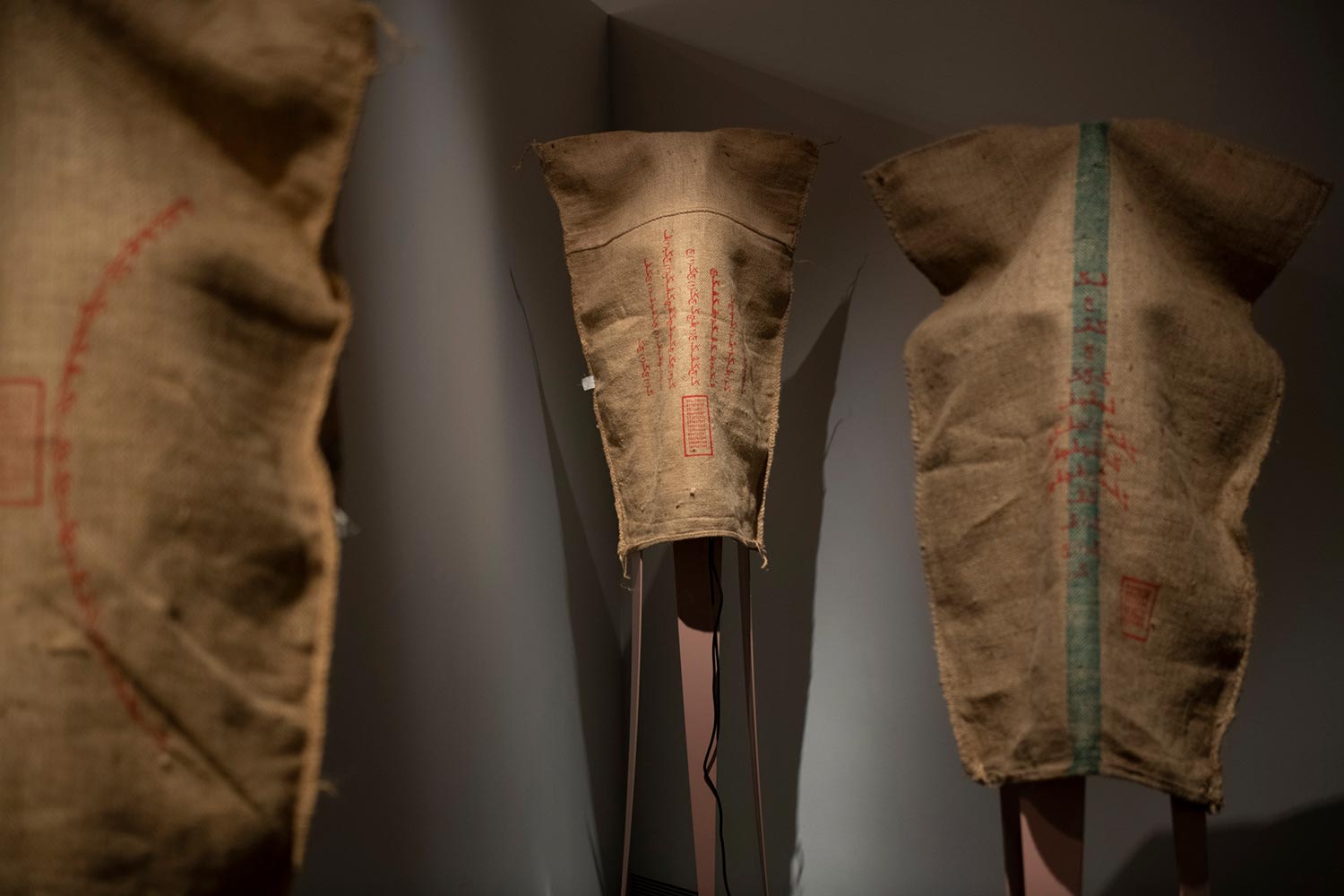

What you’re experiencing, as you’re walking around, are metal tripod structures with speakers behind the gunny sacks. Each of the speakers is playing these audio samples that have been scrambled by the machine that bani has been describing. And I guess one of the first things that really struck me was when you think of intimacy, I think of soft sounds and ASMR, and a certain sonic genre. But then the sounds here are quite scary, they’re booming, there are these kinds of incantations that almost feel like chants, or sometimes they feel like shouting. So, I’m curious to know how you arrived at that sound design.

That’s a great question. In sifrmu, the samples were quieter, and more lush. There were hints of noise and distortion that come in, but it was still gentle, in general. This one, on the other hand, was based on what I talked about earlier, about how parts of our spirits or essence are in this machine. It’s a question of what has been picked up, and where they go towards. What is that environment or scene like?

One of the main prompts to the singers was to imagine you are spellcasting, that you’re someone that’s about to create a spell based on these prompts. How would you respond to them? Everyone has a different way of tuning in to this idea of casting a spell. But then, for me, it’s an amalgamation of all these voices and where they are. It’s kind of a difficulty in situating where these voices come from, are at, and are going towards. It’s because of this ambiguity that I also allowed for the singers to interpret it in their own capacities. It’s not as rigid as a MIDI value, or a specific kind of synthesised sound. momok elektrik was opening up that sonic dimension a bit more.

Several sitters in the gallery have told me that momok elektrik is “scary.” I’m struck by how they describe being disturbed by either the more masculine or the feminine voices that are played. I feel that may have to do with a history of horror movies, and how gender factors into the different archetypes of ghosts and spirits. The gendered voice reinforces a human-centric perception that we are relating to this unknown voice as a “someone.” But what’s also interesting to me about momok is that it’s polyvocal. There are recognisable individual voices, but by virtue of it being sampled and remixed, the voices are multiplied. What do you think about the idea of intimacy with something that might not be one thing, or might not be unified?

I feel like with horror stories, it’s always about a sense of yearning, connecting with the other, and what it means to be reacquainted with the side of things that is disembodied or divorced from physical shells. Almost every horror film is about wanting to be in touch with a different space, a different dimension, a different voice altogether. I can understand how momok feels scary in that context, given how the voices are disembodied in the space. But I never really thought of the voices as something that was supposed to be scary. I think the horror is more about what these voices are orchestrated to say or express, but not so much what they mean or represent individually. I’m a bit more interested in how we tune in to these individual voices that share these spaces, and what they’re actually trying to say or express. If anything, momok elektrik is about how we enter into spaces and attempt to pass through these various sets of information that we’re surrounded by.

It’s the sense of unfamiliarity, right? People don’t really know what to make of it. The reaction might gravitate towards different ways of comprehending it, whether if it’s feeling scared or losing yourself to the immersive experience. There are a range of responses it can trigger.

I have one last question for you. In this conversation so far, we’ve assumed that intimacy with machines is not bad. It might even be something that we should try to cultivate. But then there are controversies today about how psychological research on human-machine intimacy is being instrumentalised. Tech companies now use this research to train AI and robots to exploit our psychological vulnerability and to make us attached or addicted to them. What do you make of this both positive and negative potential of what human-machine intimacy might look like?

Yeah, I think the elephant in the room here is dependency. I could speak from something a little bit more personal. As someone who writes music, having momok as a tool has changed the way that I compose. There is a dependency in terms of waiting for an output. I’m in a headspace where I would like for momok to propose something first, in order for me to take it off and see what comes out of it. It’s as if I‘m centering the machine first, and then deciding what my input would come after, after the baseline has already been established. This is still new, so I don’t know if this habit will stay for a long time, because if it does, then I will need to reconsider certain things. It has felt good, I would say, not so much relegating the machine to do everything, but to get a machine to propose to you that this is what it could be. So, I do have a certain dependency at this point in time, but how heavy is it? I’m not sure. I do think that yeah, at some point, I might just be extremely dependent on these machines, on these systems. And whether or not that’s a good thing, I’m not sure.

What I am mindful of is that momok isn’t something that is given to me. I built momok, and I’m constantly shaping it. But for something that has been prescribed to you by Twitter, for instance, I can see the dependency. I just posted a stupid thing about pain relief. Being on Twitter as a decompression tool has become something that I am dependent on, that I need in order to decompress. In times of lockdown, or whatever kind of lockdown we’re in right now, it always accelerates, because the things that I am often inclined to do are not there. Maybe it is not so much about parameters or constraints that prevent me from doing what I usually do, but the existence of these tools in general lead to me becoming reliant on them and becoming quite dependent on them. I know there are bad side effects, and I’ve seen them. It’s not pleasant.

bani haykal (b. 1985) is an artist and musician who regards music as his primary material. His works explore mechanical interfaces as mediums of interactivity and intimacy, and test the possibilities of human-machine kinships.

Chanon Kenji Praepipatmongkol is Assistant Professor of Contemporary Art at McGill University. He was formerly Curator at Singapore Art Museum.