Non-Playable Citizens: Practicing Proxy Politics in Hito Steyerl’s Factory of the Sun

09 May 2023

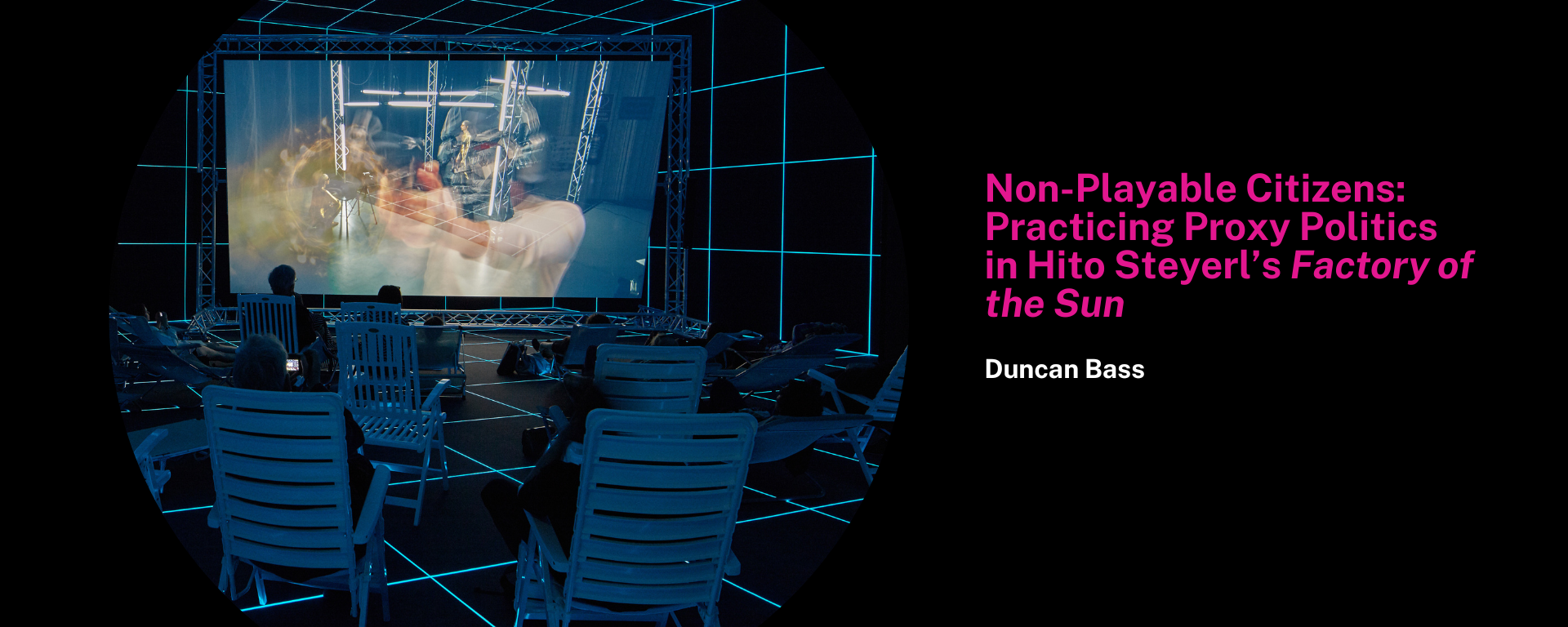

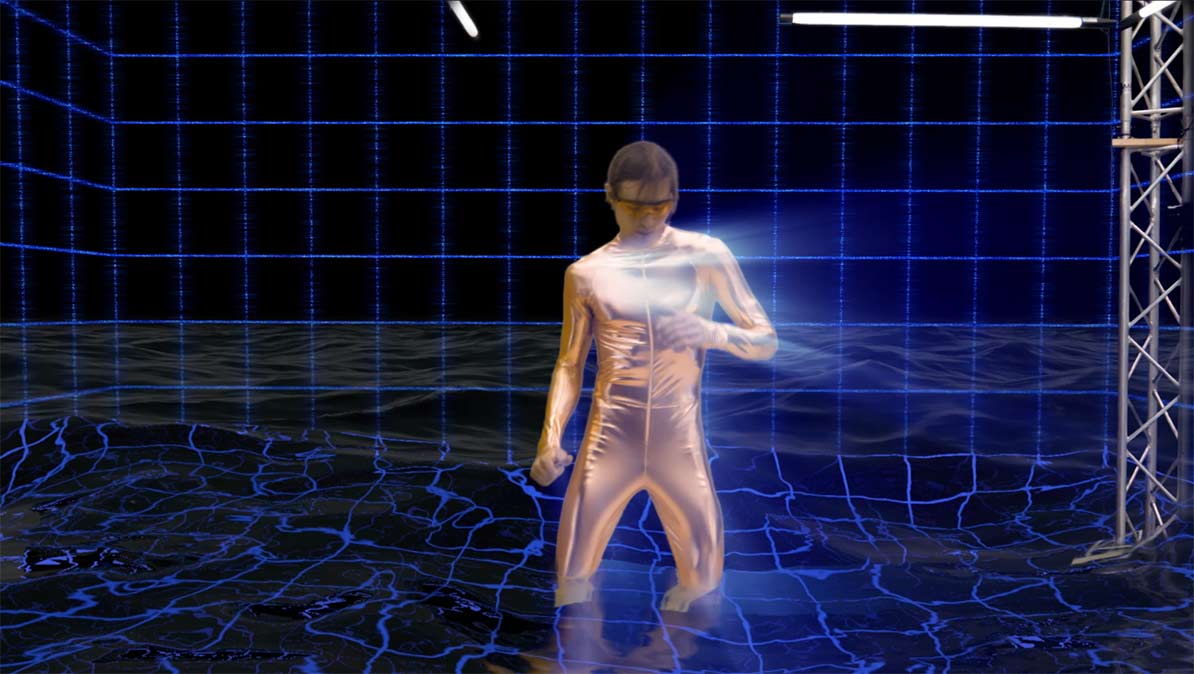

Hito Steyerl’s landmark video installation Factory of the Sun (2015) explores how the endless circulation of images in contemporary media influences our reality. On screen, the distinctions between truth and fiction dissolve in a montage of YouTube dance videos, drone surveillance footage, video games, fictitious news segments and documentation of student uprisings. This alternate reality extends beyond the screen, immersing viewers in a glowing grid that connects the physical gallery to the virtual world of the film. Moving through the semiotic layers of Steyerl’s work, this essay investigates Factory of the Sun by focusing on the central narrative of the eponymous video game, the on-screen framing devices and the artwork’s gallery presentation, to question the place of the viewer as a political subject within this mediated reality.

The Bot Manifesto

All photons are created equal!

No photon should be accelerated at the expense of others!

Resist total capture

Be a non-playable character!

Sunshine belongs to everyone!

Dunk Zombie Marxism!

And Zombie Formalism!

All politics are proxy politics!

Mez! Dazzle! Shine!

Authored by the “Bot Underground Bunch,” The Bot Manifesto interrupts the waiting screen that demarcates each loop of Hito Steyerl’s 2015 video, Factory of the Sun. Before this interruption, a timer in the upper right-hand corner of the screen counts down the seconds to the “next round,” recalling the pre-match lobby of online first-person shooter (FPS) video games. This iconic framing device exists both inside and outside the video’s enclosing metafiction, built on a montage of news reports, drone surveillance footage and YouTube dance videos, which illustrate the narrative of an invented video game and its developer. The movement between the narrative reality of the video and the reality of the exhibition space underscores the degree of agency available to the viewer, under digital authoritarianism. Moving through the semiotic layers of Steyerl’s work, this essay investigates Factory of the Sun by focusing on the central narrative of the eponymous video game, the on-screen framing devices and the artwork’s gallery presentation, to question the place of the viewer as a political subject within this mediated reality.

Shortly before the countdown clock expires, the neutral gray screen is interrupted by a “message from the sponsor,” Deutsche Advanced Execution Services. The advertisement introduces one of the founding mythologies at the core of Factory of the Sun: a 2011 announcement by CERN researchers that claimed to have measured neutrinos travelling faster than the speed of light. While the test results were later refuted—ascribed to a loose fibre-optic cable and a fast clock—Steyerl presents the potential scientific revelation as an opportunity to be exploited by finance capital. Factory of the Sun imagines Deutsche Bank as a criminal enterprise that uses the hypothetical breakthrough to conduct high-frequency trades (HFTs) faster than the speed of light. Again, the reality is simpler than the hypothesis: rather than accelerating its own trades, Deutsche Bank’s HFT branch, Autobahn Equity, was in fact accused of slowing down the trades of its clients, to gain a competitive advantage.1

“Time today is a resource that is mined to the millionth of a microsecond,” writes Steyerl.2 Whoever controls the ordering of time controls the basis of our social reality. Whether the result of a miscalibrated clock or manipulated transaction speeds, the alternate ordering of time establishes the alternate reality of the film. Within the speculative world of Factory of the Sun, accelerating the speed of light—and thus the speed of images and information—collapses the time of experienced reality, allowing images to be produced before the events they purport to document. The countdown clock, its interruption, and the video loop itself are all techniques of orchestrating time. Relating a conversation with Steyerl, João Fernandes notes that “the loop is always another way of restarting time, of reliving and reinterpreting what we have seen or experienced before.”3 Factory of the Sun transposes this re-living from the viewer to the protagonist: the loop represents not only a re-playing of the video but also a re-spawn of the in-game characters.

Zombies, Cyborgs & Bots

After the countdown, the video cites a second primary source, Donna Haraway’s The Cyborg Manifesto. A Chinese-language voiceover reads, “Our machines are made of pure sunlight. Electromagnetic frequencies. Light pumping through fibre glass cables. The sun is our factory.” A second voiceover repeats these phrases, interspersing them with the claim that “all that was work has melted into sunshine.” Invoking the historical ruptures of capitalism that Marx and Engels detail in The Communist Manifesto4 and the post-Fordist critique articulated by Haraway,5 Steyerl elaborates her thesis: in the era of information capitalism, the sites of labour, control, and collective organisation have shifted from the factory to the screen. The hypothetical acceleration of light in Factory of the Sun recalls yet another of Marx’s phrases, this time from the Grundrisse: “the annihilation of space by time.” In Factory of the Sun, the acceleration of capital circulation now exceeds all material barriers, by migrating to the virtual space of the video game, where past, present and future exist simultaneously.

This reading of Marx through Haraway enacts the refutation of “Zombie Marxism” from The Bot Manifesto. The Manifesto’s association of Zombie Marxism and Zombie Formalism further suggests a critique of the ongoing search for ideological or conceptual value in movements divorced from their historical contexts. For Mike Beggs, “Zombie Marx” represents a fundamentalist adherence to a doctrine theorised in the mid-seventeenth century which, without adaptation, is incapable of adequately engaging with the dominant paradigm of modern neoclassical economics. If Zombie Marxism can be understood as the tendency of dogmatic scholars to search for answers to contemporary economic crises in the urtext of the prophet Marx, and Zombie Formalism a market-driven co-optation of Abstract Expressionist aesthetics,6 then both can be understood as an attempt to revive the long-dead corpse of a movement, be it ideological or aesthetic. Lars Bang Larsen updates the reading of zombies in popular culture—often interpreted as an expression of the Marxian concept of alienation—for the era of immaterial labour.

To Marx the loss of control over one’s labor—a kind of viral effect that spreads throughout social space—results in estrangement from oneself, from other people, and from the “species-being” of humanity as such. […] Today, in the era of immaterial labor, whose forms turn affect, creativity, and language into economical offerings, alienation from our productive capacities results in estrangement from these faculties and, by extension, from visual and artistic production—and from our own subjectivity.7

In the internet era, the relationship between virality and alienation takes on new forms, replacing the collectivism of the zombie hoard with bot armies. Returning to Haraway, Steyerl writes, “Humans and things intermingle in ever-newer constellations to become bots or cyborgs. As humans feed affect, thought, and sociality into algorithms, algorithms feed back into what used to be called subjectivity. This shift is what has given way to a post-representational politics adrift within information space.”8

Such is that case of Yulia, who exists in Factory of the Sun as both a human being—Steyerl’s real-life assistant Yulia Startsev—and a bot. This duality is indicated by the character’s shift between her embodied voice and that of a text-to-speech program. The latter tells us that she is developing a game, also called Factory of the Sun. “But,” Yulia’s robotic voice claims, “you will not be able to play this game. It will play you.” Here, one of the leitmotifs in Steyerl’s oeuvre surfaces: the deterministic, world-building quality of supposedly documentary media. In November (2004), Steyerl reaches a similar conclusion: “In November, we are all part of the story. And not I am telling the story, but the story tells me.”

A loading bar appears onscreen, indicating a shift from the world of the programmer to the world of the fictional game. Outlining the player’s “mission,” the voiceover sketches a brief exposition, describing the player as a forced labourer in a motion-capture studio, whose movements are used to produce artificial sunshine for a corporate entity. This artificial sunlight is used by the corporation, Deutsche Bank, to accelerate its transactions. The game’s protagonist is one of four bots who escaped from the scenario before being killed in preemptive corporate drone attacks during global uprisings.

In Factory of the Sun, “bots” exist on both sides of the conflict, replacing humans in the repressive corporate regime as well as the Underground resistance. A “Bot News” segment disrupts the game introduction in the familiar visual syntax of twenty-four-hour cable news broadcasts. Further confusing the real and fictional narratives, the breaking news footage juxtaposes original images of a small drone with found footage documenting protest movements, captioned by a news ticker: “Global protests against superliminal acceleration.” Additional graphic elements provide further context for the world of the film. A panel at the bottom of the screen replicates the visual language of stock tickers, adding “Brightness” and “Contrast” to the more familiar market data of the Dow Jones Industrial Average. In a world where light operates as a commodity, these measurements take on a dual meaning. While nodding to the material conditions of the video’s production and consumption, the new data feeds also flatten that materiality, transforming “Brightness” and “Contrast” into mere signifiers. Under the regime of finance capital, light is exhausted of its practical function.

Gamespace(s)

Steyerl deploys a similar rhetorical device in the user interface of the fictional game. In-game difficulty settings are marked by philosophical positions: idealism, materialism, realism, and reality beta. The heads-up display (HUD) includes gauges for “render points,” “energy,” and a “photon score” measured in ANSI lumens (a standardised unit that measures the light output of a projector). As Yulia loads and fires her SIG Sauer in the firing range of the game tutorial, her actions update a “killfeed” that links the fiction of the game to the real world:

SIG SAUER [product placement]

Lethal Precision [tested] in Ferguson9

Electrification Object [SIG SAUER] +20

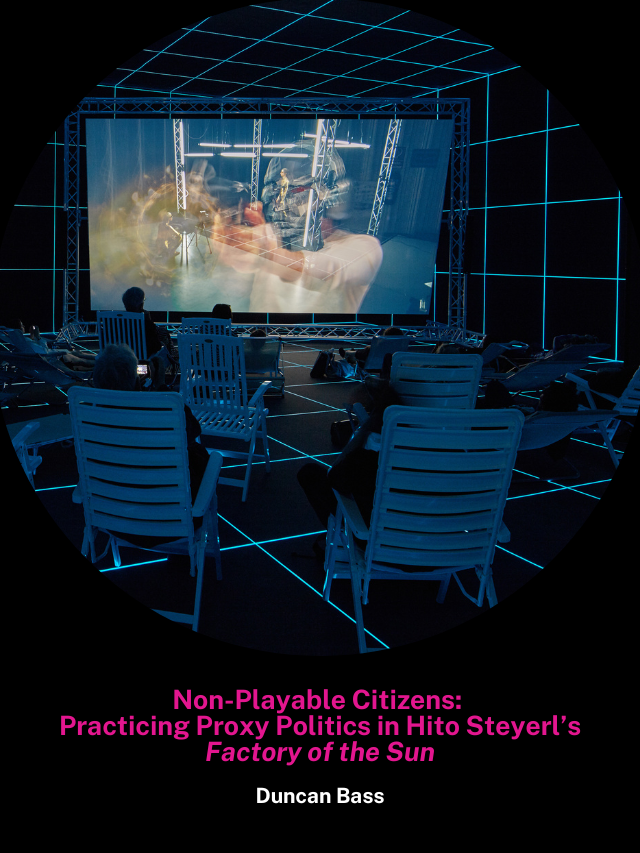

In realism mode, Yulia recounts her personal history, mixing biographical reality with the fiction of the game. The child of Soviet military officers, her family left the USSR before its collapse, and relocated to Israel. As she narrates this story, Yulia is transported from the photorealistic firing range to a 3D-rendered simulation where she destroys a swarm of Stalin Bots floating above an animated body of water. The use of simulated water, light, and reflective surfaces are significant inclusions, as these elements are notoriously difficult to render in gaming engines, requiring a large amount of computing power and graphical processing.

The space of the photorealistic and rendered firing ranges are each revealed as in-game simulations during scene transitions, when they are replaced by a luminescent blue grid signalling a virtual space—simultaneously empty and representing limitless possibilities. The grid motif repeats in a motion-capture studio, where it is used by cameras to translate an actor’s location from the physical site of production to the virtual environment. Both the grid and the aluminium truss structure of the motion-capture studio are reproduced in the gallery installation, situating the viewer in the virtual spaces of the video. Nora Alter argues that the installation positions audiences, “seated in beach chairs, as passive consumers of distraction, including distractions that hasten their own destruction.”10 But perhaps the extension of the virtual space of the game into the physical world is more akin to McKenzie Wark’s concept of “gamespace.” For Wark, video games are the dominant form of contemporary cultural expression, with game logic suffusing every aspect of life; Wark’s gamespace is the digital corollary to Plato’s Cave.11 Factory of the Sun’s installation shatters the illusion of The Cave, acquainting the squinting audience members with their lived conditions of existence. Gamespace is our reality.

In the motion-capture studio, we are introduced to the film’s second protagonist, Yulia’s brother. Under the name TSC (takeSomeCrime), he became an internet sensation by uploading dance videos from their family’s basement in Edmonton, Canada. The scene occurs via one of Steyerl’s familiar devices: the documentation of playback equipment or screens within the frame of the filmic image, a form of material montage that simultaneously recuperates pre-existing images and emphasises the presence of the screen for the viewer. Here, Steyerl replaces the VHS and DVD playback equipment of earlier films with the screen of a laptop, its internet browser opened to TSC’s YouTube page, enabling a 2011 recording of TSC—clad in a gold bodysuit and surrounded by the wood-panelled walls of his parent’s basement—to dance alongside his present self, adorned with the glowing balls of a motion capture suit and a black Soviet military beret. Yulia recalls how, as his celebrity increased, TSC’s choreography was used by fans to animate virtual Japanese pop idols. Three images of TSC, wearing costumes from his popular YouTube videos, dance alongside anime characters in perfect unison.

In “Factory of the Sun: Level 1” we find TSC and a group of dancers on the roof of a decommissioned US National Security Administration listening station atop Teufelsberg Hill in former West Berlin. In the video, the listening station has been repurposed as “Deutsche Bank Sunshine Campus,” where the “workers” are confronted by an autonomous drone. The blinking commands—“Press A for Total Capture”, “Press Y to Leak Light”, “Hold > and X to Intercept Hostile Communication!”, “Press B to Shoot Light Ball at NSA Domes”, “Rotate the joystick to Accelerate Speed of Light”—indicate the predetermined mode of autonomy available within the game. The controls delimit a binary of forced labour or toothless resistance. “Oh is it not working? But YOU are working! Own3d!”

The digitisation of the embodied act of dance is not coincidental, appearing frequently in Steyerl’s work, from chromakey-clad dancers in How Not To Be Seen (2013) to the animated police and prison guards in SocialSim (2020). Unpacking the “dancing mania” in SocialSim, Marcella Lista argues that the “grotesque dance” performed by these avatars “can be added to the long list of choreographic materials that aspire, in Steyerl’s works to actively (re)construct a ludic space in the alienated condition of our contemporary media. […] suggest[ing] bodies that are under control and bring[ing] to mind the tactics of recurrence, of reversal even.”12 Here, the act of dance functions as a form of improvisational “play,” in opposition to the regulation of the “game,” making the corporate co-optation of these movements and the lack of bodily control in Factory of the Sun particularly nefarious.

For Lista, the “undead” digital avatars that populate SocialSim and Factory of the Sun are “epitomized by the spectres and zombies that have been sidelined by an unequal society.”13 Returning to the Marxian concept of alienation and Larsen’s contemporary reading of the zombie, these digital avatars are the corpses of the contemporary proletariat reanimated by a new form of virality spreading through online social spaces. The forced labour of Steyerl’s motion-capture gulag foreshadows a recent trend whereby Amazon customers who own the company’s “Ring Video Doorbell” system request their delivery drivers perform for the device’s camera while leaving packages. Dependent on customer reviews for their livelihood, the drivers are compelled to follow the customers’ instructions, which function as scripts for producing viral videos that customers later share on social media platforms.14 Rather than a corporate overlord capturing the movements of dissident dancers under threat of death by automated drone strike, this meme expresses a more mundane and insidious form of class relations: consumers coercing working-class delivery drivers to dance under the watchful eye of privatised surveillance and the ever-present threat of robo-firing.

The rooftop confrontation is interrupted by a second breaking news report announcing the death of a protester. Before the news report, the actor Mark Waschke appears, discussing his part with Steyerl, herself in the role of director. As with Yulia and TSC, both Waschke and Steyerl appear as characters and as mediated caricatures of themselves. In the “Bot News” segment, Waschke returns as a Deutsche Bank spokesperson—the face of post-representational politics—dismissing the death of the protestor and insisting the corporation has acted within its rights. “I tell you whatever I want. This is an unlegislated area, free of liability, I open my mouth and close it again. This is democracy — this is how it works.” These scenes are intercut with those of Yulia and TSC in the motion capture studio repeatedly practicing the staged death. Each time the camera cuts back to Waschke a headline indicates that markets have increased—seventy-five, one-hundred-fifty, two-hundred percent.

Non-playable Citizens

TSC’s in-game respawn timer introduces the final scenes of Factory of the Sun, where we meet members of the “Bot Underground Bunch.” Operating outside of geographic and temporal limits, a series of multilingual voiceovers describe the circumstances of future conflicts around the globe. “We got killed in the future. We crowd your games and applications. We’re non-playable characters. We cannot be played.” These bots, the presumed authors of The Bot Manifesto, advocate a method of political resistance that runs counter to traditional game mechanics. In the world of Factory of the Sun, where “the game will play you,” they reject the role of player-operated protagonists in favour of the non-playable character (NPC), a political position that is definitionally unavailable to the co-optation and control of corporate or governmental entities.

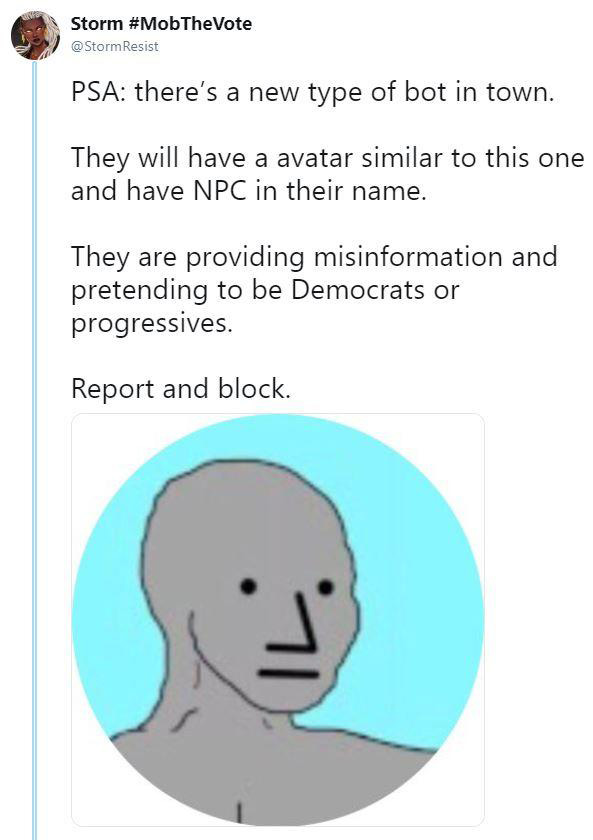

Since 2016, the figure of the non-playable character (also non-player character/ NPC) has been deployed primarily by right-wing message board users, who have used the term to dismiss and dehumanise anyone with opposing social or political views as scripted characters. Illustrated by an emotionless grey Wojak, the NPC versus main-character dichotomy made its way from 4chan to Twitter with hundreds of accounts self-identifying as NPCs ironically posting liberal talking points.15 Produced in 2015—a year before the first NPC post appeared on 4chan—Factory of the Sun preempts this discourse, framing the NPC in opposite terms to the meme: within the gamespace of contemporary society, everyone is being played except the NPC.

“The Bot Underground” and the NPC express a form of political potential articulated by Steyerl and her collaborators at the Research Center for Proxy Politics. Boaz Levin and Vera Tollmann argue that proxies are “emblematic of a post-representational, or post-democratic, political age, one increasingly populated by bot militias, puppet states, ghostwriters, and communication relays.”16 Combining legal proxies and proxy wars, proxy politics “can be seen as both a symptom of crisis in current representational political structures, as well as a counter-strategy which aims to critically engage and challenge the existing mechanisms of security and control.”17 While political bot armies function as a “contemporary vox populi,”18 influencing discourse through the introduction of confusion, disruption and noise, proxy politics are also a method of resistance. The political potential of a proxy—a bot, an avatar, or otherwise—reflects Steyerl’s position that a frequent dismissal of video games as “a capitalist conspiracy to distort reality” is both critically and morally wrong; “In fact, for the vast majority of humanity it would be great if war were just a video game. In a game, players respawn. You get shot—no problem: you can start all over again.”19 Rather than the undead threat of the alienated masses, this process of re-living offers a new form of agency suited for the political landscape of contemporary gamespace. Despite the dystopian framing of its motion-capture gulags, Factory of the Sun keeps alive the hope that systems of control and capture are also potential sites for subversion. Before the credits roll, a final in-game message appears: YOUR TEAM WON!

But the next round is about to begin.

Artist Bio

Hito Steyerl (b. 1966) is a filmmaker, artist, and writer. Her prolific practice occupies a highly discursive position between the fields of art, philosophy and politics, constituting a deep exploration of late capitalism’s social, cultural and financial imaginaries.

Author Bio

Duncan Bass is Curator at the Singapore Art Museum. His writing and curatorial projects explore the intersections of art and contemporary culture with an emphasis on the societal implications of emerging technologies and the politics of visuality.

[1] ‘In the Realm of Posthuman Documents’ in Invisible Adversaries, eds. L. Cornell and T. Eccles (Annandale-on-Hudson: CCS Bard College, 2016), quoted in Hito Steyerl: The City of Broken Windows, eds. C. Christov-Bakargiev and M. Vecellio (Milan: Skira, 2018), 178–179.

[2] “Art, a Test Site: Hito Steyerl in conversation with João Fernandes,” in Hito Steyerl: Duty Free Art, eds. A. Cruz Yábar and M. Rodríguez (Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, 2015), 163.

[3] Ibid, 169.

[4] Samuel Beckett’s 1888 English translation of The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Frederick Engels popularised the frequently quoted phrase: “All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind.”

[5] Donna Haraway, "A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century," in Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature (New York: Routledge, 1991), 153: “Our best machines are made of sunshine; they are all light and clean because they are nothing but signals, electromagnetic waves, a section of a spectrum, and these machines are eminently portable, mobile – a matter of immense human pain in Detroit and Singapore.”

[6] Walter Robinson. “Flipping and the Rise of Zombie Formalism,” ArtSpace, April 3, 2014, https://www.artspace.com/magazine/contributors/see_here/the_rise_of_zombie_formalism-52184

[7] Lars Bang Larsen. “Zombies of Immaterial Labor: The Modern Monster and the Death of Death,” e-flux Journal 15 (April 2010), https://www.e-flux.com/journal/15/61295/zombies-of-immaterial-labor-the-modern-monster-and-the-death-of-death/

[8] Hito Steyerl. “Proxy Politics: Signal and Noise,” e-flux Journal 60 (December 2014), https://www.e-flux.com/journal/60/61045/proxy-politics-signal-and-noise/

[9] Ferguson, Missouri, USA, is a suburb of St. Louis, which received international attention when 18-year-old Michael Brown, an unarmed black man, was killed by Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson on August 9, 2014, leading to widespread public uprisings.

[10] Nora M. Alter. The Essay Film after Fact and Fiction (New York: Columbia University Press, 2018), 343 (Note 65).

[11] See McKenzie Wark, Gamer Theory (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007).

[12] Marcella Lista. “Playing Machines,” in Hito Steyerl: I Will Survive, eds. F. Ebner, D. Krystof, M. Lista (Leipzig: Spector Books, 2020), 205–206.

[13] Ibid, 203–204.

[14] Megan Garber. “We’ve Lost the Plot,” The Atlantic, January 30, 2023 (Accessed March 14, 2023) https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2023/03/tv-politics-entertainment-metaverse/672773/

[15] Kevin Roose. “What is NPC, the Pro-Trump Internet’s New Favorite Insult,” The New York Times, Oct. 16, 2018. Accessed March 14, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/16/us/politics/npc-twitter-ban.html

[16] Boaz Levin & Vera Tollmann. “Plunge into Proxy Politics,” springerin Issue 3, 2015 (Accessed March 14, 2023). https://www.springerin.at/en/2015/3/proxy-politik/

[17] Ibid.

[18] Hito Steyerl. “Proxy Politics: Signal and Noise.”

[19] Hito Steyerl. “On Games: Or, Can Art Workers Think?” New Left Review, no. 103 (Feb. 2017), 101.