After the events of 18 November 2016: Artworks by Pio Abad in Singapore Art Museum’s Collection

29 Feb 2024

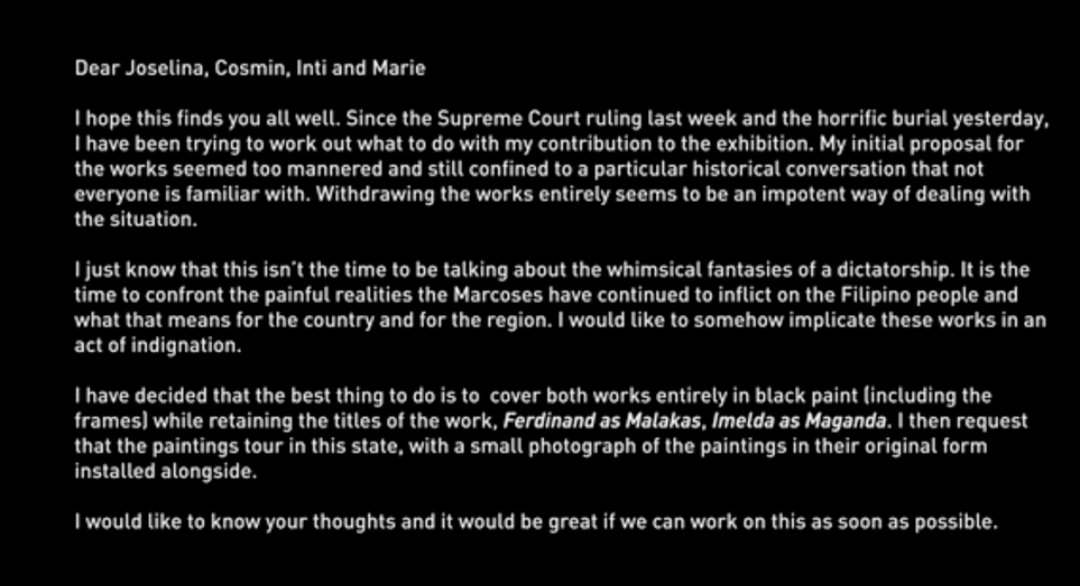

Grief is a sense of loss for futures that could have been and pasts that have slipped away. With nowhere to go, grief stretches like black paint obliterating the images of Imelda and Ferdinand Marcos in Pio Abad’s Imelda as Maganda, Ferdinand as Malakas, painted black after the events of 18 November 2016 (2014–2016). The unnamed events in the title of the work refer to the controversial hero’s burial of Ferdinand Marcos.

Ferdinand Marcos was the 10th president of the Philippines from 1965 to 1986. His second term, which began in December 1969, was marked by economic instability due to the administration’s overspending. This fiscal mismanagement sparked public demonstrations and protests. By September 1972, Marcos had declared martial law, heralding a 14-year period of authoritarian rule until February 1986 when the Marcos family fled the Philippines in exile. Martial law had sanctioned the Marcoses’ astounding kleptocracy and human rights abuses, including 3,275 extrajudicial killings and the plunder of an estimated 14 billion dollars.1 The latter was enabled through corporations that were confiscated, nationalised and placed under the custodianship of Marcos’ cronies as well as the direct extraction of wealth through financial instruments in local and offshore banks.2 According to the Human Rights Violations Victims’ Memorial Commission, a Philippine government organisation, the regime and martial law period witnessed the dissolution of the Philippines as an economic power in the region as the Philippine economy suffered its worst recession since the end of World War II. 3 Marcos’ burial in 2016 was facilitated by the Supreme Court of the Philippines and endorsed by then-president Rodrigo Duterte. His hurried hero's burial amid appeals to reverse the court’s decision to some was the whitewashing of the Marcos kleptocracy and bloody legacy of martial law—a history that in recent years through social media intervention has been increasingly reframed and posited as a golden era of Philippine progress.4

The blacked-out painting is a foil to the whitewash. It is not a surface of amnesia. It is not a blank slate with which to start anew. It is a void. The paint is a thick black shroud that insists upon a negation of the image. It is indignation. It is a demand to acknowledge what has been lost. Your eyes can only wallow in its depths, a mirror to the emptiness of a broken social contract. It is the colour of scorched earth. It is the burn-out of impassioned promises of progress and the shadowy depths of the redaction in intelligence archives.

The underlying images that are blacked out are iconic representations of Ferdinand as Malakas (The Strong One) and Imelda as Maganda (The Beautiful One)—the first man and woman according to Philippine folklore who emerged from a stalk of bamboo. The Marcoses fashioned themselves as the Mother and Father of the nation—a rhetoric embodied by this Edenic iconography of femininity and masculinity that first found form in the 1965 campaign trail of Marcos’ run for the presidency.5 The Marcoses, as noted by writers Nik de Ynchausti and Vicente Rafael, had a flair for marshalling the power of history and actively recrafting national and civil progress through their figures as the ‘Father and Mother’ of the Philippines.6

This primeval portrayal of the conjugal dictatorship and its aspiration to present the Marcoses as “the originators of the circulation of cultural and political power”7 has confounded the artist Pio Abad (b. 1983) over the last decade, and this set of paintings which once resided in Malacañang Palace has been a refrain in his work. As it travelled as part of the exhibition Soil and Stones, Souls and Songs curated by Cosmin Costinaș and Inti Guerrero and presented at De La Salle-College of Saint Benilde’s Museum of Contemporary Art and Design in 2016 as an installation8, Imelda as Maganda, Ferdinand as Malakas, painted black after the events of 18 November 2016 was displayed alongside a photograph of the artist’s father smiling in the Presidential Study at Malacañang Palace, taken by his mother on 25 February 1986 when, as part of the People Power Revolution, they entered and explored the 54-room palace that was once the abode of the Marcoses.

This photograph is important. Not only is it a referent for the images that were painted over, but also an inheritance that Abad has described as the ‘genesis’ of the chimeran and expanded research project that has evolved into The Collection of Jane Ryan & William Saunders (2014–ongoing). Abad’s parents were Butch Abad, Budget Secretary under the Benigno Aquino III administration (2010–2016) and Batanes Representative Dina Abad. As he recounts in his projects and his recent exhibition Fear of Freedom Makes Us See Ghosts at Ateneo Art Gallery in 2022, they “met as student activists and community organizers, committed to the cause of the social democratic movement in the 1970s under the growing threat of the Marcos dictatorship. Their work as trade union organisers subjected them to strict surveillance and threats of arrest.”9 In an essay about his practice, he notes:

This photograph was taken by my mother on the evening of the 25 February 1986. A few hours before, Ferdinand and Imelda were chased out of the presidential palace and boarded one of Ronald Reagan’s helicopters for a reluctant Honolulu exile. My mother and father, the figure on the right, were two of the first protesters to enter the private chambers. This photograph, I believe, is one of the earliest documentations of that exact moment when the public façade of Malakas and Maganda collapsed, and the people they had been oppressing for two decades suddenly had access to the sordid private life behind these misrepresentations.10

The photograph of his father, taken by his mother, along with the reproductions of the oil paintings Imelda as Maganda, Ferdinand as Malakas, can be read as totems across his projects that represent a narrative compass structuring his interrogation of the legacies of the Marcoses. He first presented these works in his MFA graduation show titled 1986–2010 at the Royal Academy Schools in London. The exhibition focused on the life and images of objects of the conjugal dictatorship as they intersected with Abad’s own life. It included speculative artefacts such as the seashell-decorated CCTV camera that Imelda Marcos could have owned as well as artefacts such as a seashell-encrusted clock that was a discarded gift from Imelda Marcos to Abad’s father in 2010.

Following his MFA exhibition, the first iteration of The Collection of Jane Ryan & William Saunders, titled Some Are Smarter Than Others (2014), at Gasworks (London) was based on Abad’s study of the catalogues of two Christie’s auctions held in New York on 10 and 11 January 1991. These auctions, commissioned by the Presidential Commission on Good Government (PCGG), aimed to sell 78 lots of Georgian and Regency-era silverware, 97 Old Masters paintings of inconsistent quality and dubious provenance. The photograph and the paintings were presented again in this exhibition—pointing to a strong familial undercurrent. The Christie's sale was intended to fund the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program, which Butch Abad was tasked with implementing in 1990. In addition to the paintings and photograph, the exhibition included a replica statuette of the primeval Filipino couple Malakas and Maganda, photographs of the paintings and silver reproduced from the Christie’s catalogue as well as framed reproductions of historical material, among which, a Christie’s document about the silverware, and a photograph of his parents in the presidential palace before portraits of the conjugal dictators as the primeval Filipino couple.

Concurrent with the Gasworks exhibitions, Abad also presented The Collection of Jane Ryan & William Saunders at the Jorge B. Vargas Museum at the University of the Philippines in Manila. An edition of the work is part of the collection of the Singapore Art Museum (SAM). The work comprises 98 sets of postcards, featuring reproductions of the Old Master paintings sequestered from the Marcoses and sold by Christie’s on behalf of PCGG. Designed to be indefinitely reproduced for each installation, the postcards are presented across a monumental plinth. On one side, each postcard depicts a different painting from the sale, while the reverse side adapts news coverage of the collection. Visitors could take the postcards with them. The installation encouraged a democratic consciousness in its viewer by being highly participatory. Abad noted that this was one of the first instances that a Filipino public was engaging directly with the Marcoses’ collection of artworks. The exhibition, which was a return to his alma mater before he left for further studies in the UK, was also his first museum exhibition in Manila.

Aptly titled after the aliases used by Imelda and Ferdinand Marcos when they first opened bank accounts with Credit Suisse in Switzerland in 1968, The Collection of Jane Ryan & William Saunders is an ongoing project and series of exhibitions and artworks that Abad has ‘collected’ under this framework that, on one hand, actively reconstitutes the kleptocracy of the Marcoses through the portrayal of the excessive consumption of Imelda Marcos and, on the other hand, includes objects that have been inspired by the personality-driven propaganda of the conjugal dictatorship and, in particular, Imelda Marcos. The collection is a foil to the Marcoses’ privatisation of public wealth. Like his father’s photograph, Abad’s work makes visible the scale of the Marcos kleptocracy and democratises knowledge of a collection that is yet to be entirely rediscovered. Essentially, it returns to the public what the Marcoses had bought as private possessions. Through reproductions as postcards, Abad’s attempt to reclaim the democratic potential of art is a politics of visibility, wherein the radical political potential of the artwork is to make evident and visible what powerful actors would hope to reframe and hide.

The strategy of visibility enables Abad to spotlight the abuses of politicians. In 2014, in the face of false accusations raised by political opponents that his father Butch Abad’s Disbursement Acceleration Program led to misappropriations that benefited the family, Abad wrote a rebuttal on Rappler citing his own personal struggles as an artist:

It is interesting then that the reality felt quite different. When my father was allegedly reaping the benefits of PDAF, I was flipping burgers in Burger King Queen Street Train Station.

When the kickbacks from the BatanElCo project were supposedly setting me up for life, I was living in a mice-infested flat where the discovery of non-animal excretions in our doorstep was not an uncommon occurrence.

Even now, having achieved relative recognition, my wife and I haven’t stopped working hard. If we had had millions stashed away somewhere, I would now have a lot of explaining to do to my in-laws who fed and sheltered us while I was pursuing my Master’s. 11

Read against this intimate and extreme form of personal transparency, the painting painted over in black can be interpreted as a self-evident and radical object of transparency as much as it is a performative gesture of obscuring an image. The latter is documented through a video that chronicles Abad’s deliberations in painting over Imelda as Maganda, Ferdinand as Malakas. The video begins with the art handler calling out, “You're a dead man. You’re a dead man Marcos,” as he lifts Ferdinand as Malakas off the wall to paint it black. The declaration is made almost as if Marcos himself needed to be reminded to stay in his grave. In the video, we can hear Abad instructing and directing the gesture as necessary with the curator Joselina Cruz. His comments are punctuated by exclamations of elation at the effect of the black paint. At one point, Cruz and Abad discuss how this is possibly Abad’s first video art. These moments of transparent levity cloak an unease.

Abad did not know it in the video yet, that the black paint would become the turning of a global tide, and a bitter sense that visibility and representation are politically impotent strategies. Donald Trump ascended to the office of the American presidency in 2017. In 2018, the Cambridge Analytica scandal broke, revealing how our digital communities were used to profile us and sway elections. This shift in world order was derived from the Marcos rule and its dynamics of political control, which originated from the Philippines through networks and bureaucratic agents affiliated with the Marcoses. Christopher Wylie, the whistleblower behind the Cambridge Analytica scandal would go so far as to describe the Philippines as “a petri dish” where the company tested out strategies that it later implemented in Western countries, drawing parallels between the United States and the Philippines: “Filipino politics kinda looks a lot like the United States…You’ve got a president who was Trump before Trump was Trump, and you have relationships with people close to him with SCL and Cambridge Analytica. And you have a lot of data being collected – the second largest amount of data after the United States being collected [is] in the Philippines.”12

The Kingmaker (2019), a documentary by Lauren Greenfield and a project that relied in part on Abad’s research13, implies that the burial of Ferdinand was part of Imelda’s designs and aspirations to rebrand the Marcos legacy and install her son Bongbong as the president of the Philippines. In 2019 and 2020, the Filipino news outlet Rappler published their investigation into the Marcoses’ use of social media for their own historical revisionism.14 These subsequent revelations in the popular press were an unmasking of the complex systems of structure and power behind the political façades used to rally people. In 2016, when the black paintings were made, neither the public nor Abad was aware of the increasing political and social engineering that was underway the world over to reframe history and political projects in order to shape electorates.

When Abad presented a survey of his artworks in Fear of Freedom Makes Us See Ghosts at Ateneo Art Gallery from 19 April to 6 August,15 Bongbong Marcos was elected to the presidency in June 2022. A retrospective view of this series of events suggests that the 2016 hero’s burial of Ferdinand Marcos was a turning point in the return of the Marcos family to the presidency. Reading Imelda as Maganda, Ferdinand as Malakas, painted black after the events of 18 November 2016 against Abad’s artistic voice and practice, especially in relation to The Collection of Jane Ryan & William Saunders, which is defined by a politics of making visible the shady dealings and contradictions of the pro-Marcos propaganda, the black paintings can be interpreted as an evolution or as a moment of critical reflexivity in Abad’s practice.

The black painting is an avant-garde trope as much as it has become a symbol to rally the public. From Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square (1915) to hashtag critiques of racism featuring blacked-out squares on Instagram, the black square has been described as a “one-size-fits-all gesture of performative—and, often abortive—protest, participated in by private users and fast food chains alike.” 16 An almost ubiquitous reference now, the blacked-out painting or black square is a symbol full of meaning and affect, but also of impotent political effect. The work’s inherent emotive response captures the shock and devastation to what some may perceive as a public acting against its own democratic interest, a public afflicted by an amnesia akin to cultural dementia. Coined in 2018 by historian David Andress, the term ‘cultural dementia’ refers to a form of “forgetting, misremembering and mistaking the past” across society that emulates the experience of dementia where “anger, bitterness and horror coexist with fond illusion and placid self-absorption. Practical action becomes impossible…Historical stories abound; but as deployed in public debate they are often little better than dangerous fantasies, constantly at risk of abrupt and jarring collision with reality.”17

Abad’s practice has deployed visibility to try to stem the tides of populism and technological currents that erode history and lull a public into a state of cultural dementia. His critical mobilisation of “collections” uncovers, reclaims and makes visible the chequered histories of appropriations and transactions that have defined the Marcos kleptocracy and the Philippine government’s subsequent attempts to (re)claim them as public wealth. These histories are interwoven with Abad’s personal history. As alive as these histories are and as urgent as their representation in Abad’s own practice, recent developments has pointed to these representations as inherently impotent in the face of technologies and bureaucracies that now operate behind the networked façade of images and slogans of a political campaign.

Yet, the inclusion of these two artworks, The Collection of Jane Ryan & William Saunders and Imelda as Maganda, Ferdinand as Malakas, painted black after the events of 18 November 2016, in Singapore’s national collection —therefore, held as a cultural asset in an international financial and technological hub at the crossroads of resurgent Cold War histories—speaks to their potentiality as historical artefact and the complexities that underline the politics of visibility and conceptualism across Philippine modern and contemporary art history. Such that the grief-laden gesture of obscuring the iconography of kleptocrats, resists the possibility of permanent erasure.

Artist Bio

Pio Abad (b. 1983) is an artist whose work is concerned with the personal and political entanglements of objects. His wide-ranging body of work, mines alternative or repressed historical events and offers counternarratives that draw out threads of complicity between incidents, ideologies and people. Deeply informed by unfolding events in the Philippines, where the artist was born and raised, his work emanates from a family narrative woven into the nation’s story.

Author Bio

Kathleen Ditzig is a Singaporean art historian and curator. She studies modern and contemporary Southeast Asian art and its intellectual trajectories in relation to global histories of capitalism, technology and international relations. She received a PhD from Nanyang Technological University in 2023 with a dissertation titled, “Exhibiting Southeast Asia in the Cultural Cold War: Geopolitics of Regional Art Exhibitions (1940s-1980s)”. She obtained a MA from the CCS Bard in 2015 and a BA in Art History and Asian Humanities from UCLA in 2010.

Endnotes

1Nik de Ynchausti, “The Tallies of Martial Law,” Esquire, 24 September 2016, https://www.esquiremag.ph/politics/opinion/martial-law-tallies-a1576-20160924-lfrm4 (accessed 31 January 2024).

2Jason C. Sharman, The Despot's Guide to Wealth Management: On the International Campaign against Grand Corruption (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2017).

3“Was martial law good for the Philippine economy?,” Human Rights Violations Victims’ Memorial Commission, https://hrvvmemcom.gov.ph/was-martial-law-good-for-the-philippine-economy-2/ (accessed 9 March 2022).

4“‘Golden age’: Marcos myths on Philippine social media,” France 24, 8 May 2022, https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20220508-golden-age-marcos-myths-on-philippine-social-media (accessed 31 January 2024).

5Talitha Espiritu, Passionate Revolutions: The Media and the Rise and Fall of the Marcos Regime (Athens: Ohio University Press 2017), 80.

6Vicente L. Rafael, “Patronage and Pornography: Ideology and Spectatorship in the Early Marcos Years,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 32, no. 2 (1990): 282–304, JSTOR: http://www.jstor.org/stable/178916 (accessed 27 June 2023).

7Pio Abad, “The Collection of Jane Ryan & William Saunders: Reconstruction as ‘Democratic Gesture’,” in Over and Over and Over Again: Reenactment Strategies in Contemporary Arts and Theory, eds. Cristina Baldacci, Clio Nicastro, and Arianna Sforzini, Cultural Inquiry, 21 (Berlin: ICI Berlin Press, 2022), 37–46, https://doi.org/10.37050/ci-21_05 (accessed 31 January 2024).

8Stephanie Bailey, “Soil and Stones, Souls and Songs,” Artforum, https://www.artforum.com/print/reviews/201706/soil-and-stones-souls-and-songs-68752 (accessed 31 January 2024).

9“Fear of Freedom Makes Us See Ghosts,” Pio Abad, https://www.pioabad.com/fear-of-freedom-makes-us-see-ghosts (accessed 18 July 2023).

10Abad, op. cit., 38–39.

11Pio Abad, “Artist Pio Abad speaks up for his father, Butch,” Rappler, 31 May 2014, https://www.rappler.com/voices/ispeak/59315-artist-pio-abad-speaks-up-butch-abad/ (accessed 31 January 2024).

12Paige Occeñola, “Exclusive: PH Was Cambridge Analytica’s ‘petri dish’ – whistle-blower Christopher Wylie,” Rappler, 10 September 2019, https://www.rappler.com/technology/social-media/239606-cambridge-analytica-philippines-online-propaganda-christopher-wylie/ (accessed 31 January 2024).

13Author’s conversation with the artist, 2022

14Sofia Tomacruz, “Bongbong Marcos asked Cambridge Analytica to ‘rebrand’ family image,” Rappler, 16 July 2020, https://www.rappler.com/nation/bongbong-marcos-cambridge-analytica-rebrand-family-image/ (accessed 31 January 2024).

15“Pio Abad: Fear of Freedom Makes Us See Ghosts,” Ateneo Art Gallery, https://ateneoartgallery.com/exhibitions/pio-abad-fear-of-freedom-makes-us-see-ghosts (accessed 1 January 2023).

16Andy Zuliani, “Black Square: Petty Waste, Aesthetic Spamming, and the Politics of Obstruction,” Oxford Research in English 12 (2021): 124, https://oxfordresearchenglish.files.wordpress.com/2021/07/trash.pdf (accessed 29 January 2024).

17David Andress, Cultural Dementia: How the West has Lost its History, and Risks Losing Everything Else (London: Apollo, 2019), 1–2, 7.