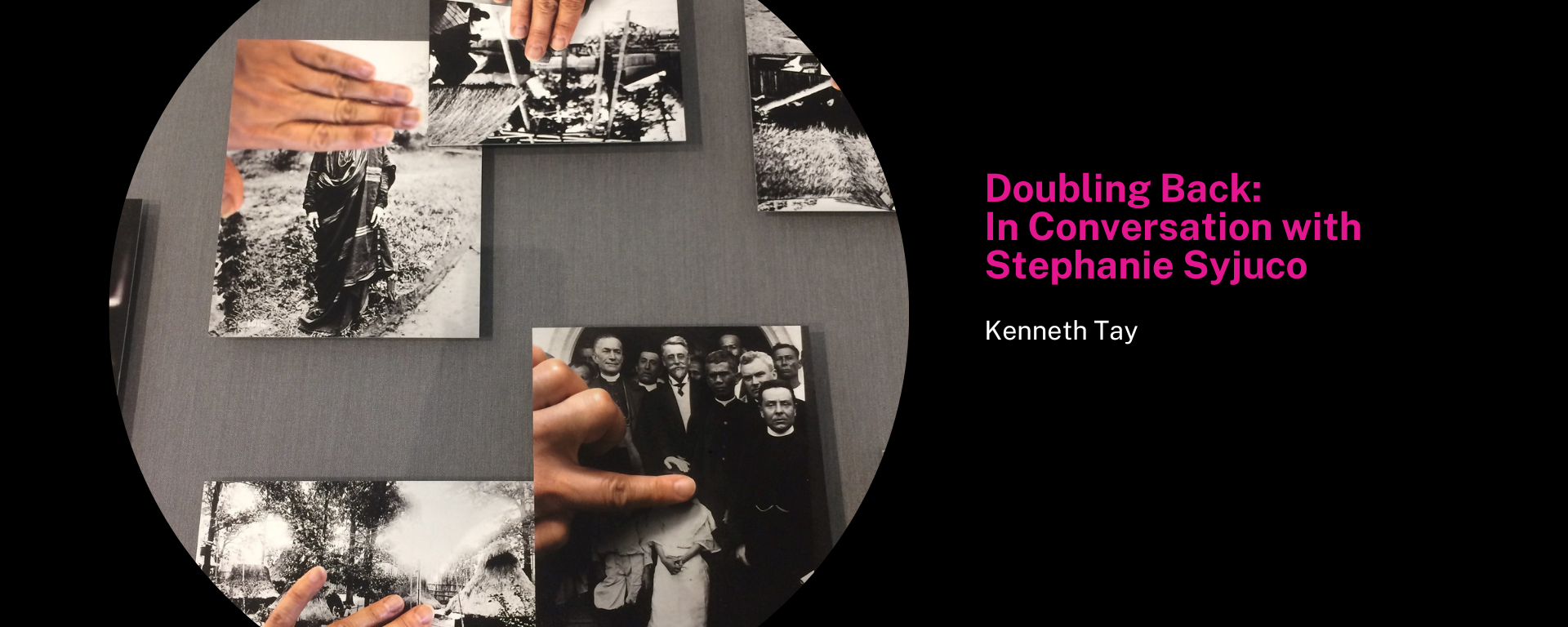

Doubling Back: In Conversation with Stephanie Syjuco

09 May 2023

The following is a conversation between Stephanie Syjuco and SAM curator, Kenneth Tay, which first began in April 2022 as part of the extended commentaries for the exhibition catalogue of Living Pictures: Photography in Southeast Asia. Between February and March 2023, the conversation was extended to go beyond its original focus on the work Block Out the Sun (2019), to touch on some of the artist’s earlier works and the broader aspects of her practice.

Could you describe the process and experience that led you to the fictional Filipino Village at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis? It seems like it all began from a stereo-card found in an antique shop somewhere in Asheville, North Carolina. Could you also tell us why you happened to be at both St. Louis and Asheville; and, for those of us who are not familiar, what cultural significance do these two locations have in the cultural history of the United States?

I knew loosely about the display of Filipinos at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, but hadn’t spent time doing research into it until two things interestingly converged. I was in Asheville, North Carolina, which is located in the Southern part of the US, to participate in a think tank on American crafts. Asheville is a historic centre for American craft, and in some ways also functions as a kind of nativist, romantic Americana heritage site in the Blue Ridge Mountains of the Appalachians. Tucked away in a small antique shop was a box of vintage stereo cards — an early form of visual technology that simulates a 3-D pictorial process. Shuffled in with a variety of other cards on different early-twentieth century images, was a stereo card of Filipino weavers wearing traditional garb, and the caption was labeled “Bagobos Women in the Philippine Village,” and dated 1904. At first, I was excited to find something that appeared to be a document of a traditional Filipino craft — it converged interestingly with my purpose in Asheville, thinking through both heritage and contemporary craft processes. I purchased the card for $3, triumphant that I had found a relic of Philippine culture buried in the heart of America, and even posted an image of it on social media, much to the pleasure of viewers who exclaimed over the beauty of the women’s craft, and pride in this cultural work.

But something about the stereo card was really odd, and the more I stared at it, the stranger it seemed: there was a sign above the weavers’ heads that read “Native Cloth,” as if it were being shown in a formal display area, and not located in a village somewhere in the Philippines. A quick Google search turned up the matching dates of 1904 and the St. Louis World’s Fair, and I realised that I had purchased a tourist stereo card sold as a curiosity to Fair visitors. And what I thought was a romantic vision of my cultural heritage was actually a staged performance of an American empire showing off the spoils of its newly-acquired colony, the Philippines. Further research evidenced that the images of these women weavers were just part of much larger collections of images made of the over 1,200 Filipinos imported into the United States and put on display at the Fair, and that their presence and photographs would be used as pedagogical tools to the general public as justification of the benefits of American colonisation and racial “uplift.”

It was then that I realised that the amnesias and cultural whitewashing of these types of American photographs obscured the power dynamics of what was really going on, and made me question how ethnographic images taken under asymmetric conditions can be seen today as “beautiful,” when in fact, they should be read as highly problematic, staged and fabricated. As a Filipino American raised in the United States, [I find] there is a dearth of representation and also a tendency to cling to visual forms of heritage, even if that representation is found in the heart of the empire. What does it mean when I learn about my own heritage only through the images made by the empire?

Almost concurrently to finding this stereo card in Asheville, I was invited to participate in a solo exhibition at the Contemporary Art Museum in St. Louis, by curator Wassan Al-Khudhairi. Wassan was keenly interested in supporting a site-responsive project, and knowing that there had been the “Philippine Village” at the World’s Fair, set up research visits in which I had access to multiple historical archives in St. Louis: The Missouri Historical Society, The St. Louis Public Library, The Mercantile Library and the St. Louis Science Center. From there, I was able to sift through image after image of photographic documentation of the “Village,” most of it framed in an uncritical way, and come to terms with how, through mass orchestration, Filipinos were made to play their parts. The Philippine peoples were not alone in being put on display. Other “human zoo”-type displays of Native Americans and other indigenous peoples across the world were also heavily trafficked at the Fair.

Because of the backdrop of the Philippine Village, including nipa huts, traditional boats and other structures built by imported craftspeople, many of the images appear at first glance to be taken overseas in the Philippines. But the irony of them being taken in St. Louis, considered a Midwest “heartland” of America, was not lost on me. In some cases, you could see “America” peeking into the frame, and in others, there are white onlookers gawking at Filipinos, just off to the side.

In 2019, the effects of the Trump Presidency were also in full swing, with the enlarged nativist rhetoric, the targeting of non-white Americans and immigrants alike. I had shifted my practice in 2016 to begin directly addressing American amnesias head-on, in order to point to white supremacy as an ongoing structural problem. The St. Louis World’s Fair is a beloved historical event, and there is a sense of pride still evident in and around it — as if it’s easy to overlook how it functioned to racially categorise peoples. By locating the safe internal American zones of Ashland, North Carolina and St. Louis, Missouri as two key places/ moments in the formation of this work about empire and colonisation, I’m attempting to bring directly into the geographical center of the US a concern usually purposely located “outside” of itself—namely that the impetus for the wars, the subjugations, and the crafting of the colonisation of the Philippines is actually located directly in the US, and not outside of it. In the American imagination, the Midwest is constructed as a romantically pure place, a place of innocence, hardworking individualism and solid American values, when in reality, it is constructed in a way that positions itself outside of the “Other” — the Other being the immigrant, the brown, the foreign, the non-native, the Filipino.

Why did you choose, in the end, to intervene into these pseudo-ethnographic images of newly imported Filipinos? Why did you allow these images, however problematic, to recirculate once more — albeit through your own presence as a Filipino-American artist? It seems to me like it was quite important for you to do this work in the political climate of the United States back in 2019.

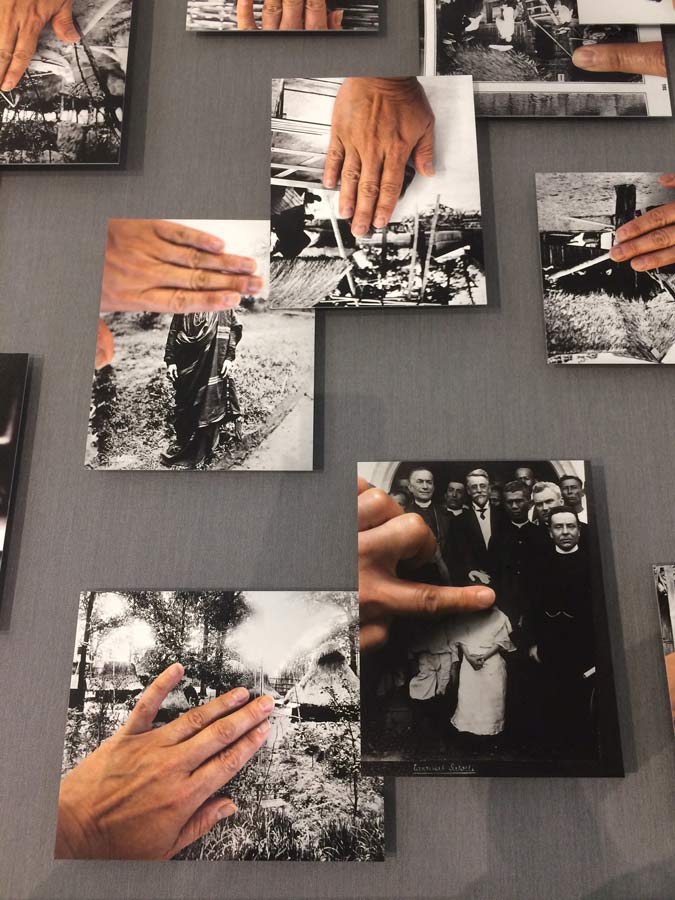

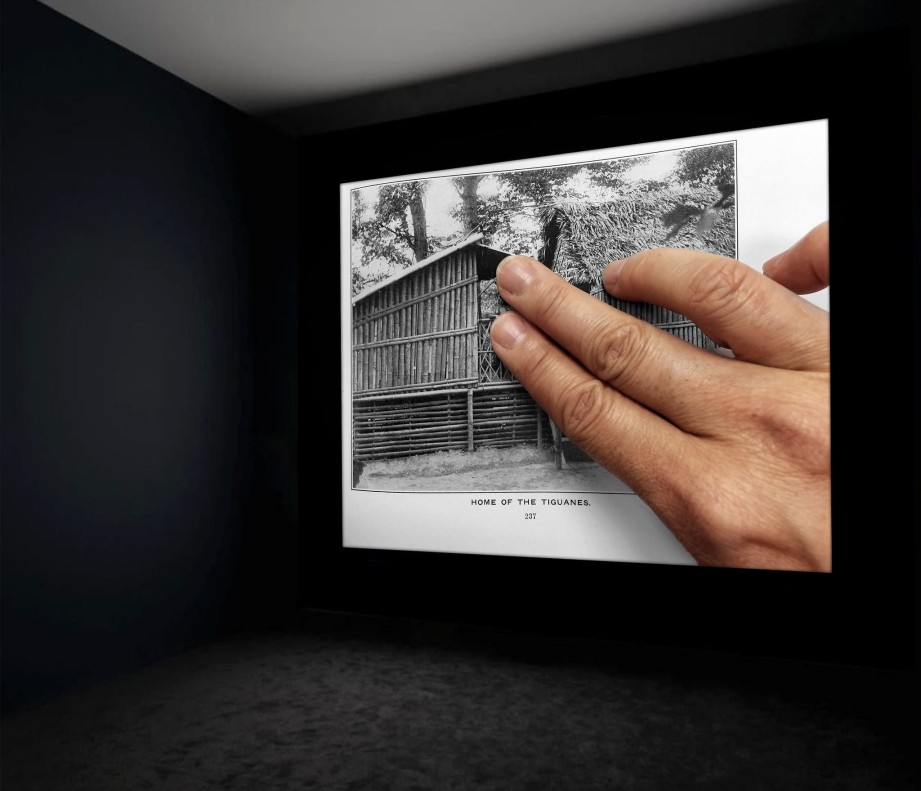

Archives are intensely problematic yet important spaces for collective memory. Problematic in that they record a heritage based on what was considered important at the time, and that includes racist, violent and disturbing realities — often without a contextualisation that challenges them as being just neutral documents. By rephotographing my hands partly obscuring the original images, I’m attempting to not erase them from memory or erase them from the archive, but to prevent them from functioning within the narrative they were given — namely that these individuals would be conscripted to showing, in perpetuity, the dominance of empire, in its ability to display others as savage or needing colonisation, in order to progress as a people. Because that was the intent of the World’s Fair display — not to show beauty or cultural complexity (although perhaps some could read that as a side effect), but to show off these people as symbols of conquest.

So why show these images again, now? Interestingly, most Americans have no knowledge about this early contact moment with the Philippines, or that the Philippines was once ever an American colony, and the site of a war that took over 100,000 Filipino lives. If anything, the Philippines does not exist in the American imagination at all, so I felt it was important to resuscitate this history in some way. And because, over a hundred years after these photographs were taken in the US, we are still confronting a distorted vision of America that posits a nation of “insiders” and “outsiders” — a country that is being overrun with hordes of brown immigrants who are not equal to white, European, civilised society. In attempting to excavate why we as a country are still turning this over and over, I wanted to look back at some of the earliest images of Filipinos taken in America, and see how they also fed into similar positionings of Native Americans and Black Americans — that we were all lumped into varying degrees of not meeting standards, of not belonging. In the United States, white supremacy is a particularly insidious vision in that it has structured our archives, our institutions, and our very technologies of seeing and being seen (i.e., photography and imaging technologies) through its lenses, and yet presents itself as enlightened and democratic. With a contemporary resurgence in white nationalism, I wanted to challenge that vision from a root of historical engagement, and to show that white supremacy has been a long-standing, ongoing project.

Could you tell us why the title Block Out the Sun? I’ve always been intrigued by the title of the work.

As a photographically-based work, I was thinking about how light generated by the sun is the literal way that these original images were made: by light bouncing off a subject, into a camera, and then onto emulsion. I find irony in the motto “let there be light” — as if shining light on something will lead to truth or enlightenment, when in the medium of photography, images were used to conscript and assign value, when used as ethnographic tools. Block Out the Sun references my literal blocking of the light using my own hands 100 years later on these images, and also considers what it means to deflect the image itself, and prevent it from functioning with its original intention.

Block Out the Sun exists both as a display vitrine and as a video installation. Could you share with us what differences and affordances you were exploring through the use of two different media for the work?

Although the two works use similar images (the vitrine installation version has 30 images, while the video version uses about 50 images), they function very differently. The vitrine forces the viewer to walk around a display that mimics a kind of museological presentation in order to see the entire selection, while the video presents a slideshow-like, time-based sequence, along with a soundtrack. The soundtrack is important because it represents an array of 100 years’ worth of camera shutter sounds, sourced from publicly-accessible sound databases, and attempts to implicate the viewer in the act of looking and even taking pictures.

The video version can also be presented quite large as a projection, which makes my hands seem like powerful interventions, as opposed to modest ones. The vitrine installation, on the other hand, allows the viewer to take in all 30 images at once, but is also interestingly presented with a multiplicity of my hands across the surface, blocking and denying visual absorption. I see these two versions as complementary bookends to the project, but also as standalone articulations of re-presenting and intervening in archival, colonial-era images.

In a way, these two versions of Block Out the Sun remind me of the very stereo card itself that led to the work. I want to come back, briefly, to the technology of stereoscopes and stereo cards, because I think it’s an interesting metaphor to think through parts of your practice too. Firstly, stereo cards and stereoscopes work by using two images shot from slightly different angles; and we only perceive a sense of depth by converging our looking through the stereoscope. In that moment, what are essentially two different images become “mistakenly” viewed as one, albeit with a sense of depth. Of course, I’m sure this optical illusion added further to the American curiosity of the colonies. But there’s something there too, in this conflation of two different images, that I think also speaks to some of your earlier works like the Body Double series (2007)? There was also a similar search for the Philippines, and a doubling that occurs in that work!

I appreciate that you bring up the visual phenomena of stereo cards again. They were developed in the nineteenth century, and quickly became a way to present to the American and European public an overarching vision of different landscapes and cultures. We could even identify this vision as an imperial one, since many stereo card collections focused on a tourist-like gaze, along with captions that positioned the subjects as exotic oddities, or somehow in opposition to Western culture. Doubling (and even tripling) comes up in my work often, both as a metaphor for the dual function of needing two eyes to create a 3-dimensional image, but also as a nod to the Du Bois-ian notion of double consciousness and how the colonial/ post-colonial subject has to inhabit two distinct forms of knowledge at once.

Leaving the Philippines for a bit, I wanted to talk to you also about another earlier work of yours: Phantoms (H__RT _F D_RKN_SS) (2011). Why Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, and why did you reprint and reformat the digital bootleg versions of it? Maybe this comes across as a little left-field, but I’m really curious how you think these gestures relate back to your practice today.

Phantoms (H__RT _F D_RKN_SS) included a series of paperback books that I printed using the exact text downloaded from different online versions of Joseph Conrad’s famous novel, Heart of Darkness. Because of the nature of how these texts were reproduced online (strange line breaks, odd font sizes, and even in some cases, online advertisements sprinkled throughout), what resulted were sets of paperback books that deviated from the original novel and presented to the viewer a mutated form.

I chose this text because it is known as the standard critique of colonialism (in this case the Belgian Congo) as told through a Western lens. Conrad’s novel subsequently went on to inspire the 1979 Frances Ford Coppola film Apocalypse Now, using Vietnam as a contemporary American substitute, which interestingly, is connected to my video trilogy Body Double, in which I crop and re-edit American films of the Vietnam War that were actually shot in the Philippines.

But my textually-mutated Conrad paperbacks start to point to how different forms of reproduction can create their own variety and even different forms of narratives within what is supposed to be one text. Just like how Conrad’s Heart of Darkness becomes a general parable or folly of colonial empire, how it is told and retold through subsequent adaptations can change and even corrupt its original intention. Empire itself is constantly shifting shape, and when we point to a novel written in the 1800s as a pinnacle of a period of empire, we divert the gaze onto a historical event as opposed to focusing on how its effects are still with us, and are still unfolding. I’m not critiquing Conrad as much as I’m trying to show that the aims of his novel are still very much in the present, contemporary online glitches and all.

This early work of mine also went on to have visual echoes in works like Neutral Calibration Studies (Ornament and Crime) (2016), and Dodge & Burn (Visible Storage) (2019). In these installations, I rampantly downloaded both historic and contemporary images — many of them low-resolution and pixelated — and brought them back “to life” as prop-like objects. I want history to not be shuttered into notions of “the past” but to be infected with how we digitally view and access images.

Lastly, in our earlier conversations together, you’ve mentioned that you try to go back to Manila and the Philippines as much as you can. While most of your work seems to focus on the broader histories and politics of the United States where you are based, you’ve also managed to show quite recently in the Philippines, too. Could you share with us the experience you had with the show Crime and Ornament organised by Silverlens, last year? And perhaps what your future plans might be—if any—regarding the Philippines and the region?

Showing artwork in the Philippines at Silverlens with other contemporary Filipinx artists has been an amazing experience. The sets of concerns in the US and the Philippines are parallel but also different, and I’m still processing how audiences may approach my work differently, depending on country and cultural context. Within the United States, my work is usually positioned as part of an “immigrant experience” narrative, whether I want it to or not. There is something very specific about the American demand for cultural representation when looking at artists of colour, that doesn’t exist in the same way in the Philippines — for obvious reasons — and reflected through the US’ long history of excluding non-white artists from the dialogue, coupled with the recent push for better representation of so-called minority artists. I’m not saying that the audience in the Philippines is less political or less demanding, but I feel viewers there are not necessarily looking at works by non-white artists to solve or address centuries of injustice, or educate them on “diversity” (ugh). I appreciate the breathing room that I feel in the Philippines to not have to legibly address being Filipinx — because it’s already a given, and it can become much more complex in how that reality could manifest. One can even choose not to address it, and have the luxury of audiences not reading all sorts of cultural markers into every little thing. To be honest, I feel American audiences can be lazy and myopic in this way, and it’s exhausting and limiting on the work. For instance, in the US I have to stress that my work is not about my Filipino identity, but it’s actually about the white gaze — and those are two entirely different concerns.

My last show at Silverlens, “Crime and Ornament” was a group show with UK-based artist Pio Abad, timed to coincide with the 2022 presidential election in the Philippines. The focus was on forms of visual protest in the United States and the Philippines, and the mediated nature of historical memory and despotism. It was a great way to bring together a dialogue of concerns and try to link how authoritarianism in both countries is a growing threat. This international dialogue is what I want more of, and why working with Silverlens as well as connecting with other Filipinx and Filipinx-diasporic artists is so exciting for me — it takes my work out of a narrow scope of possibility that can sometimes happen in the US, and puts it into a more complex (and complicated) reality of global concern. I’m happy to share that my relationship with Silverlens has deepened, and we will be formally working together in the future, and planning a solo show sometime in 2024!

Artist Bio

Stephanie Syjuco (b. 1974, Manila, Philippines) works in photography, sculpture and installation, moving from handmade and craft-inspired mediums to digital editing and archive excavations. Her projects leverage open-source systems, shareware logic and flows of capital, in order to investigate issues of economies and empire.

Author Bio

Kenneth Tay is Assistant Curator at the Singapore Art Museum. His research interests include global infrastructures and their media histories.