Grotesque Chimeras and Shifting Compositions:

The Empowering Borderless World of Heri Dono’s Two Party Border

29 Feb 2024

Wayang kulit possesses a rich, intricate history that remains significant in Indonesia today. Known as a storytelling vehicle, the theatrical art has been used in many contexts, most notably in politics, to put forth the dominant cultural and sociopolitical ideas of the time. The extensive plot, characterisation and setting of wayang have made the art adaptable and relevant across many centuries. Artists have well observed this cultural phenomenon and blended this artform into their oeuvre to enhance their visual language. Significantly, contemporary Indonesian artist Heri Dono (b. 1960) is esteemed for adopting the elements of wayang in his work, to critique Indonesia’s political climate of the late 20th century, through which he masterfully utilises the ambiguity of wayang characters and composition to inspire social empowerment in the midst of political turmoil.

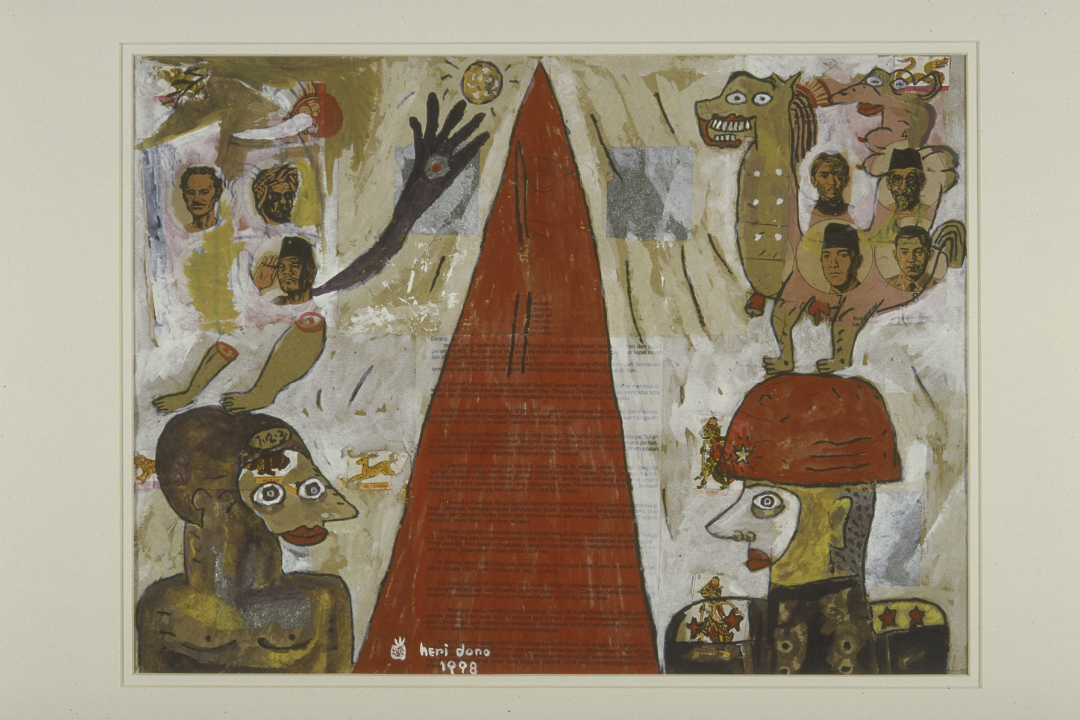

Dono’s 1998 painting Two Party Border illustrates two seemingly opposing members of society: the scarlet, decorated military man and the fragmented, naked layman. The work was made during Reformasi, an era marked by the resignation of the infamous authoritarian president, Suharto, which ultimately led to an arguably less tense, democratic sociopolitical environment for the Indonesians. It is important to note the political underpinnings of this work to understand how Dono’s painting seeks to empower rather than polarise society then. From 1968 to 1998, Indonesia was ruled by Suharto and witnessed grim years of massacres, excessive control and crippling inequality during his dictatorship. During his term, the arts were heavily regulated with “censorship laws [that] were implemented with harsh punishment for journalists and artists who publicly voiced their critique of the government.1 As such, artists sought alternative ways to bypass these laws and express their political sentiments, eventually realising the power of wayang to covertly articulate their non-conformist stance. Since the precolonial era, wayang has been used by “Javanese rulers…to disseminate information to their subjects.2 However, the purpose of wayang evolved during the Dutch rule to become a “medium to convey subtle criticism of colonial powers” instead.3 To this day, wayang continues to be used for both purposes—propaganda and critique —thereby creating a special Indonesian visual language that is often riddled with dual meanings. It was not until the fateful May of 1998—after months of protests and failing propaganda smokescreens—that Suharto resigned. Dono’s painting depicts this period of turmoil, where the authorities and public were fighting for control over the fate of the country, utilising the most powerful communicative tool in Indonesia’s history to elucidate the power play of the respective parties. He reclaims the iconography in Two Party Border and exploits the multifaceted nature of wayang characters and composition to rightfully emancipate the public after years of disillusionment and disempowerment.

First, Dono invents his own wayang characters, creating his own lore that may or may not be based on the traditional elements of wayang kulit. Aside from the obviously human characters presented in the work, a grotesque monster looms over the military man. It is a figure not seen in traditional wayang kulit: the Chimera. Where wayang kulit would typically portray animals such as deer and elephants, Dono depicts a creature from Greek mythology instead. Other bizarre creatures with disproportionately long, bendy arms or fleshy arms for legs are also featured in his other works. However, what makes Dono’s Chimera different from his other fantastical creatures is the significance of this mythological beast. The iconic Chimera is visually known for its “head of a lion in front, the head of a goat in the middle, and a serpent tail,”4 with variations emerging throughout centuries of Western art history. Yet, it is known for its intrinsic paradoxical features. Dono’s Chimera manifests with the usual heads of a lion and a goat; however, the animal displays abject expressions, instead of its usual fearsome features. The lion's head is noticeable only because of its scantily drawn mane, while its face is made up of almond-shaped, white eyes and a disembodied mouth, delineated by red lips and an array of huge teeth. Meanwhile, the goat is identified by its elongated facial structure and horn, bearing similar features to the lion with its big red lips and almond-shaped eyes, rendering both animals grotesquely human. Unlike the usual Chimera, the serpent tail is absent in Dono’s depiction. In addition to the disquieting nature of the animal, two phalluses and visible breasts protrude from its body, their bright red colour drawing the attention of the viewers. Dono’s Chimera is endlessly contradictory and non-conventional: male and female, lion and goat, animal and human.

Due to the strict censorship laws during Suharto’s regime, Dono realised that it was “easier to communicate directly to the public through a traditional medium such as wayang” as “conventional fine art…was too abstract.”5 Even then, he had to obtain permission from the government to perform wayang which compelled him to create a plot for a fake ‘traditional’ show initially, only to later change it to his crude, actual plot with “puppets engaged in sexual intercourse, which is never depicted in the traditional wayang performances.”6 The Chimera, explicitly endowed with (human) reproductive body parts, is intentional in highlighting the jarring difference between Dono’s wayang and traditional wayang, as well as to emphasise the perverseness that is rife in Two Party Border. Plastered on the Chimera are photos of Indonesian national heroes, positioned as if they were riding the abject creature. The spotlighted Indonesians are Dr Soetomo, the co-founder of the first native political society in the Dutch East Indies (top left); Hj. Agus Salim, Indonesia’s Minister of Foreign Affairs from 1947 to 1949 (top right); Supriyadi, former Commander of the Indonesian National Armed Forces who rebelled against the Japanese in 1945 (bottom right); and, lastly, the first president of Indonesia, Sukarno (bottom left). These figures, emerged from different ideological backgrounds, are ultimately united by a single goal: Indonesia’s independence. By including the photos of these famous faces, Dono breaks all previous censorship rules, no longer wading the treacherous waters of covert political commentary. He offers this formulation of figures for criticism, be it positive or negative. Astride the mutated, grotesque figure of the Chimera, these political personalities are also inextricably tied to the crude, perverse and contradictory qualities of the paradoxical animal, thereby evoking the criticality of their differing ideologies. Furthermore, Indonesian viewers would be able to recognise Dono’s Chimera as an outlier in the pantheon of wayang characters, accentuating the conspicuous peculiarity of the Chimera and the collage of political figures, prompting the viewers to confront the disjunctive composition and gradually realise the criticality that lies within the work. With such explicit commentary being nearly impossible months before this painting was made, its creation during Reformasi signifies the courage of artists to dismantle prior censorship laws, reclaiming their agency in (re)imagining, (re)appropriating and (re)using iconographies around them—especially of a traditional artform like wayang that has been known for centuries as a powerful democratic tool—to express the sentiments of disempowered civilians. Therefore, Two Party Border exemplifies the reflexive potential of Dono’s unconventional wayang characters as he imbues his work with explicit politics, giving voice to the critical lay Indonesian, and mirroring the increasing democratisation throughout Reformasi.

Another integral element of wayang to note is the composition of the set. The wayang set is controlled by the dalang (puppeteer), who presents the narrative according to his perspective, from behind the screen. Puppets are designated to the left or right side of the dalang based on their characters: the halus, good personalities, are usually positioned on the dalang’s right side while the kasar, evil personalities, are positioned on the left side.7 This classification can be explained through the Mahābhārata, an ancient Indian epic that revolves around two groups of cousins, the Pāṇḍava and Kaurava. The Pāṇḍava are the halus characters, always triumphant and pious while the Kaurava are kasar, constantly losing and driven by “greed, lust and chicanery”.8 In other words, the composition of a wayang set establishes the winning and losing parties, visually indicating the power imbalance that exists within the plot to the audience. Most importantly, just like how the arts were regulated during Suharto’s reign, the composition of the wayang set can depend on the dalang and authorised regulations, influencing the portrayal of who is righteous and who is wicked.

Typically, as per regulations then, Suharto’s New Order would be depicted as the righteous Pāṇḍava, relegating his opposing party, Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI), to the left as the Kaurava. Although PKI no longer existed during the New Order regime, Suharto used its image as an ideological threat to strengthen his rule, and to stress that “the political Right had become victorious and the political Left was evil and had lost.”9 Generally, in Indonesia, right-winged political parties tend to be more Islamist and conservative, while the left-winged parties advocated secularism.10 Even though it is difficult to categorise Suharto’s party, Golkar, in the left–right political spectrum, its inauguration into the ‘right’ position was still significant as it would mandate an absolute win, advancing the idea of Suharto’s party being, literally, always right. Yet, Dono undermines this propaganda in Two Party Border by positioning the virtuous layperson to his right and the decorated military officer to his left. The Chimera hovers over the military officer, while the layperson is dominated by dismembered limbs and portraits floating in empty space. Even though the military officer and Chimera seem to appear more intimidating, their losing left position diminishes any threatening aura that exudes from either of them. Comparatively, the right-positioned layperson’s disembodied legs in empty space could signal the freedom that the common folk won from Reformasi, tipping the scales of power again. Although the composition of Dono’s Pāṇḍava seems disorganised, scattered with fragmented body parts, in contrast to the orderliness of the Kaurava, the artist laces the painting with the duality of wayang—what you see is not necessarily what is true. He criticises Suharto’s rampant surface-level propaganda by hiding multiple meanings within his work, turning censorship on its head and appropriating the illicit symbols of those years to create a work that unapologetically celebrates the power of the people.

In addition to celebrating democratised power, a crimson triangle separates the two characters, reminiscent of the gunung (mountain) in a wayang set, the presence of which “marks the beginning and end of a performance, the change from a scene to another.”11 Against the backdrop of Reformasi, Dono’s artwork visualises the ‘end’ of Suharto’s rule with his crimson gunung and captures the transfer of power, rightfully erasing Suharto’s association with the Pāṇḍava. Most significantly, the artwork explores beyond the political climate of Indonesia as he includes a list of world events with the gunung, marking the universal power transition to the global civilian. The piece of paper listing the events is positioned at the centre of the work, seemingly plastered behind the crimson gunung—its translucency drawing focus to the paragraphs. The striking crimson hue traditionally symbolises anger12 and urgency, compelling viewers to lean closer to read. The events listed are not merely world politics of the decades leading to the turn of the century, such as the inter-Korean relations and the Tibet-China conflict, but also athletic achievements of Mike Tyson and Carl Lewis, illustrating the different scales of sociopolitical developments around the world. As such, these events, collaged into the gunung, are critiqued, mourned and even celebrated in the background, quite literally, of Indonesia’s political turmoil. This suggests that not only is Indonesia changing, but the rest of the world as well. Fascinatingly, the translucent aspect of his collage medium recalls the translucency of wayang kulit puppets and props when held behind the screen, in front of a light source. Following this trail of thought, the crimson gunung is similarly ‘illuminated’ by the events of the world—collaged behind the gunung yet emphasising the gunung’s presence and vice versa. The world events can be read as a hopeful light, that even the smallest of changes is possible. By listing events preceding Reformasi, the artwork generates a sense of anticipation, suggesting a domino effect as events cascade towards the inevitable Reformasi. Hence, Dono’s work does not confine itself to the Indonesian viewer/context but extends beyond it, reflecting on the inexorable march of global change in the late 20th century.

Conclusively, Two Party Border is a work that restores and reveres the power of the people in the midst of Indonesia’s 1998 political revolution, employing ambiguous wayang elements to overturn the iconography of Suharto’s rule. Dono’s unconventional use of the Chimeras and the complex nuances of wayang’s composition reveals the influence of the public that had been suppressed for close to 30 years, heralding a new sociopolitical era for Indonesia. In retrospect, contemporary Southeast Asian art has long been a compelling mode of expression, conflating the region’s rich history, culture and environment into the iconic works we experience today. Its art transcends the confines of its vernacular aesthetics, articulating the untranslatable vigour and sentiments of its people to the rest of the world. As Dono puts it, “art is not only for exploring beauty but to give new consciousness to people.”13

Artist Bio

Heri Dono (b. 1960) is a Yogyakarta-based contemporary artist that is well for his installation works, many of which were inspired by his experiments with wayang, the complex shadow puppet theater of Java. In many of his installations and performances, Heri Dono effectively makes use of ‘performativity and interactivity potencies’, so that the works are involved in complimentary dialogs with their audience.

Author Bio

Syakirah Aqilah is an English Literature and Art History student at Nanyang Technological University (NTU). Her research interests include the carnivalesque in contemporary Indonesian art and the symbiotic relationship between art and literature. She was an intern at the Singapore Art Museum between May and July 2022.

Endnotes

1Julie Romain, “‘All Art is Part of the Same Constellation’: A Conversation on Craft and Artistic Practice with Heri Dono,” The Journal of Modern Craft 9, no. 2 (2016): 185.

2Helen Pausacker, “Presidents as Punakawan: Portrayal of National Leaders as Clown-Servants in Central Javanese Wayang,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 35, no. 2 (2004): 213.

3Ibid.

4Avi Kapach, “Chimera,” Mythopedia, https://mythopedia.com/topics/chimera (accessed 23 March 2023).

5Romain, op. cit., 187.

6Ibid.

7Esplanade, “Children's Guide to Wayang Kulit,” Esplanade: Theatres on the Bay Singapore, https://www.esplanade.com/offstage/schools/learn/guide-to-wayang-kulit (accessed 28 January 2024).

8Pausacker, op. cit., 214.

9Ibid, 219.

10Vedi R. Hadiz, “Imagine All the People? Mobilising Islamic Populism for Right-Wing Politics in Indonesia,” Journal of Contemporary Asia 48, no. 4 (2018): 566–583.

11Esplanade, op. cit.

12Ibid.

13Romain, op. cit., 188.