“We can let people narrate their memories as they remember them”

In Conversation with Tiffany Chung

01 Sep 2022

Maps are documents that survey land masses and often contain jarring contradictions. When thinking about contemporary artists who work deftly with maps and cartography today, Tiffany Chung’s practice comes to mind. An established and prolific artist-researcher, a few of Chung’s works are in the Singapore Art Museum’s collection. Despite the thirteen-hour time difference between Singapore and Houston, we managed to find a suitable time to chat with the artist and spoke over Zoom. The following text is an edited transcript of that call. Using Chung’s works in our collection as touch points, we discuss her enduring interest in cartographic forms, the long-term work of The Vietnam Exodus Project, and the things that have been keeping her occupied. This interview was conducted in May 2021.

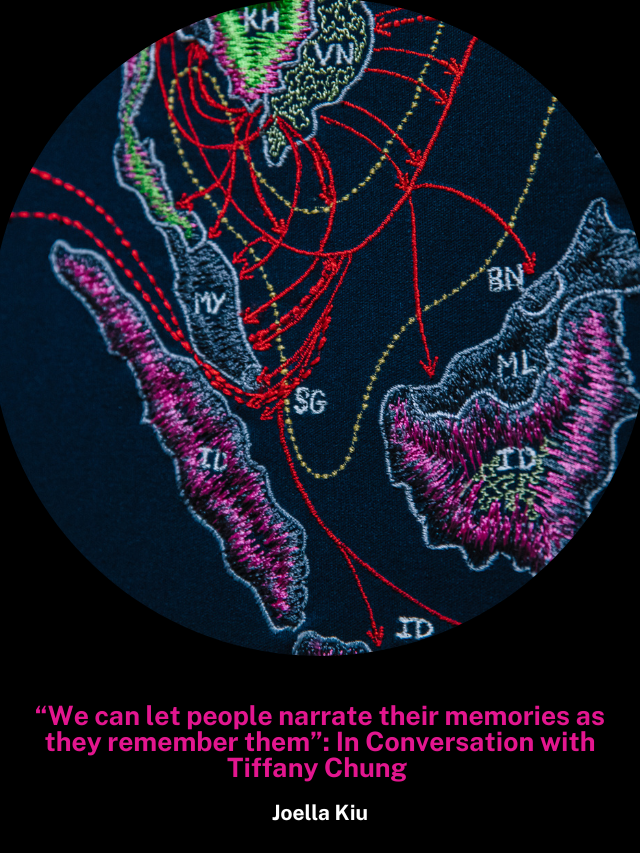

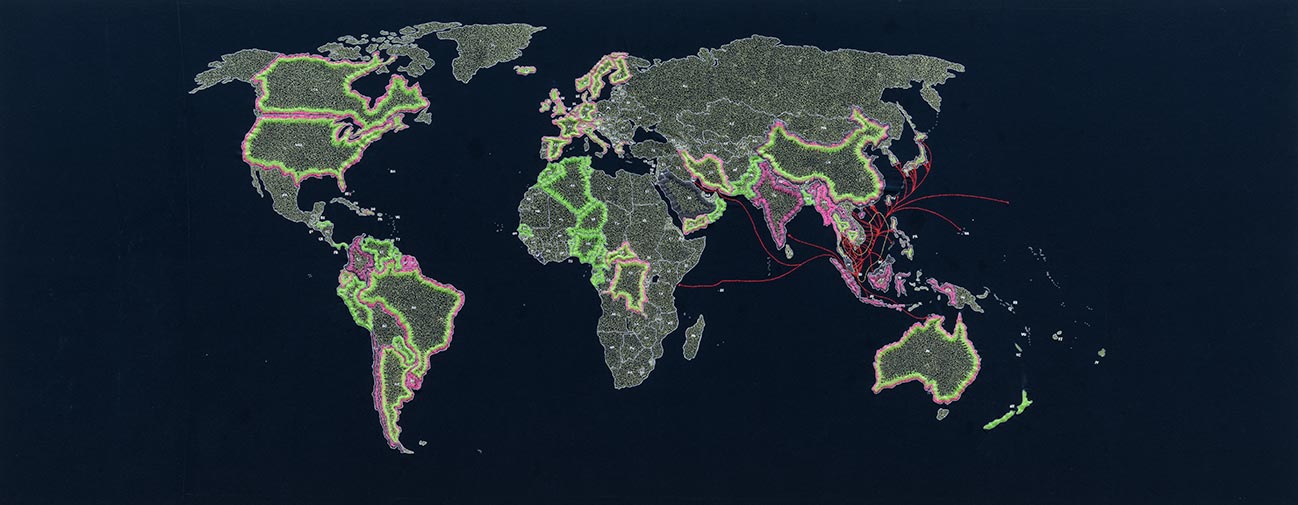

Within your research and practice, you’ve drawn upon maps to great effect in the reconstruction, remediation, and re-enactment of fraught and pluralistic histories. In particular, I’m thinking of two examples that we have in the Singapore Art Museum’s collection: Remapping the Vietnam Exodus: refugee numbers and camp locations in Asia, and Reconstructing an exodus history: boat trajectories, ports of first asylum and resettlement countries. Why have maps emerged so prominently within your practice both as an accomplice and as a tool?

I discovered cartography as a critical tool back in 2006–2007 when I began doing research into the urban development of Saigon. I came across some urban planning maps of various development projects in the city. These maps gave me an anticipation and a glimpse into how the city was going to be developed, particularly where rural and urban intersect. In some of these areas, gigantic land craters were formed pervasively due to soil extraction for land reclamation in other booming construction sites. The spatial shifts in the city happened with skyrocketing real estate values, which were propelled rapidly with foreign investment pouring into urban megaprojects, leading to population displacement. I was witnessing all of this and wanted to understand how the spatial shifts had been planned out. As an artist, you’d look at an image and study all the details. Going beyond the surface, you’d begin to question what exactly you’re looking at. Re-rendering these maps allows me to pay very close attention to these projects and how new areas were being mapped out. It’s important to note that a space is not a blank canvas that we can just draw a plan and build upon. The history of Saigon goes back hundreds of years, as the city was founded in 1698. Given that context, how might these city plans be carried out and how would those projects affect the city’s inhabitants? I began with an interest in urban planning and wanting to learn about my city, and maps were the visual aids. As cartography has become an integral part of my practice, I’ve grown more conscious of the power that lies behind cartography and all the political negotiations or indications that a map might embody. It has been a very eye-opening process, to say the least.

There are so many historical layers to cities, as you’ve mentioned. Instead of encapsulating this, maps carve out land and flatten terrain. When seen from an aerial perspective, they also prioritise one vantage point over another. There’s been quite a bit of discourse around the limitations of cartography, and the failure of maps or mapmaking. Having considered these limitations in your practice, have you found the failure of maps freeing, restrictive, or a little bit of both?

I don’t approach mapmaking with the intention of utilising its traditional functions as how we see maps. As I continue to render and re-render maps on my own, my interest in the subjectivity of the maps is quite inevitable. Yes, maps can carve out space and flatten terrain—we can't deny such power and the authority of maps. Benedict Anderson wrote about the three institutions of power: the census, the map, and the museum. Historically, colonial powers used cartography to claim territories, enumerate local populations, and map out their fantasies on distant topographies. In the case of Vietnam, maps have also been used to erase communities and spaces throughout different periods in its history, well before and after the French colonial time. Nation-building rhetoric demands that we expand through conquering, erasing and building anew – and a map can be a gaze from above, giving an illusion that no one and nothing has ever existed before us. I’m conscious about using maps to subvert institutional power. I often work with maps and archives because these are the sites of political struggles, where we can contest. By including oral histories or voices from the ground, we can rewrite history as histories so that they include multiple perspectives. We can let people narrate their memories as they remember them.

Now that we’re discussing archives and archival research, I'd also like to spend some time talking about your experience doing a residency at NTU CCA as well. I understand that you looked into Singapore’s history with Vietnamese refugee camps during your residency with the NTU Centre for Contemporary Art in 2014. Could you tell us about your experience of looking through the archives, the sort of materials you uncovered, and perhaps even the gaps in memory (institutional or collective) you noticed?

For my residency at NTU CCA, I was looking into the history of Singapore as a British colony, and how the British conducted their civilising mission throughout British Malaya. I was also working on The Syria Project (2012–ongoing) that later was presented at the exhibition All the World’s Futures, at the 56th Venice Biennale. During the residency, I just decided to go to Pulau Galang in Indonesia, looking for the sites of former Vietnamese refugee camps with Viet Thanh Nguyen. Although most of the structures have since collapsed, the remnants are still there. They even have a small museum dedicated to these histories. When I came back to Singapore, I told artist-archivist Koh Nguang How about my trip there. Koh told me he knew about the 25 Hawkins Road camp in Singapore and offered to take Viet and me to see the site, but there’s nothing left of it there anymore.

When I came back to Vietnam, I started working on The Vietnam Exodus Project (2014–ongoing). In fact, I’d worked on this subject before in Scratching the Walls of Memory (2009–2010) but emotions ran deep. Working on The Syria Project and having a chance to visit the sites I mentioned above really prompted me to make a detour and confront Vietnam’s recent history—the conflict, the aftermath, and the refugee exodus. All the research I’ve been doing for this project was not done in Singapore. In fact, if I remember correctly, all the documents or records of the Vietnamese refugees who passed through Singapore were discarded following the closure of the camp—there are no archives of the Vietnamese refugees in Singapore.

It’s really shocking to hear that these documents were discarded—not just misplaced. There’s a certain level of intentionality to actively discarding documents.

There wasn’t an official archive on the Vietnamese refugees in Singapore to begin with, as there was never a plan to resettle the Vietnamese refugees locally. Only the refugees who had already secured a resettlement offer from the flag states of the merchant ships that rescued them at sea were allowed to stay in Singapore for up to 3 months, awaiting resettlement. While many Vietnamese refugees ended up staying in other Asian countries such as Hong Kong, Thailand and Malaysia for an extended period, Singapore was a transit place in the truest sense. Also, there is a vast amount of paper records linked to every refugee that passes through a refugee camp. When I was doing research at the UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees), I discovered reams of records. A lot of materials from regional camps were sent to the UNHCR HQ in Geneva. But I heard that the records from the 25 Hawkins Road camp were either burned or buried.

The archival materials you uncover during your research are then mingled together with personal stories and narratives. In a previous interview, you described this approach as a combination of “academic research with ethnographic fieldwork.” Could you expand on your methodology, and some of the relationalities or tensions you’ve encountered whilst conducting fieldwork or consulting archives?

I no longer use the term “ethnography” to describe my approach, just “fieldwork.” My research process consists of two parts: library research and fieldwork. Library research simply means I’d have to look for and access data and relevant information available in an area of inquiry. This of course can be done at libraries, archives or online. I’ve gathered materials such as archival records, media reports and scholarly studies and analyses on various aspects: policies, data and statistics, refugees’ experiences etc. on Vietnamese refugees through library research, including at the UNHCR in Geneva. Fieldwork, on the other hand, is when I do participant observation to collect oral histories and cross-check materials gathered during my library research against these anecdotes.

For the Hong Kong chapter of The Vietnam Exodus Project, I was able to connect with a group of former Vietnamese refugees living in Hong Kong and made multiple trips to the city for fieldwork between 2015 and 2018. I first met with this community over a picnic in Tuen Mun and told them about my research. However, when I do participant observation, I don’t just show up with a camera and a list of questions. It’s about connecting with people, listening to their stories, and trying to be a part of their community. I respect people and don’t treat them as subjects. I instead wait for them to tell their stories in their own time. Many of them actually have an urge to tell their own stories after so many years have passed. I don’t interview or record those moments, but take mental notes and memorise them as much as I can. And I write down everything as I remember it, upon going back to my place.

The first iteration of the Hong Kong chapter of The Vietnam Exodus Project was presented at Art Basel Hong Kong in 2016. That brought me face-to-face with a lot of ethical decisions. I was dealing with the histories of and hardships faced by Vietnamese refugees, and showing it at an art fair was challenging. I went through a period where I questioned the ethics of doing just that. Eventually, I decided that it was important that this history was reactivated in Hong Kong. Art Basel Hong Kong was a good setting for that because the fair draws a substantial local and international audience. After the work was installed at Art Basel Hong Kong, a couple of human rights lawyers approached me. These lawyers had worked on the cases of Vietnamese refugees, and following that introduction, we worked together for two or three years.

Throughout our conversation, you’ve touched on the work you’ve done with the Hong Kong chapter of The Vietnam Exodus Project a couple of times. I’d love to spend some time on that because I'm interested in the intersections between your art, the geopolitics it responds to, and the reverberations of said geopolitics on the lives of refugee and vulnerable communities. You have, for example, successfully championed the case of stateless Vietnamese refugees in Hong Kong. Would you say that your role as an artist has given you unique insight into these issues, and do you see this activism as an extension of your artistic practice, a completely different facet, or simply a responsibility?

I don't see myself as an activist in the traditional sense of the term: being at the front lines, shouting slogans, or holding up banners. I think being an activist involves a big commitment and certainly, bravery. I just see that activism is an inevitable aspect of my work, like part of a package. My work has also been informed by social scientists and thinkers such as Hannah Arendt, Andreas Huyssen, Erik Harms, David Biggs, and Viet Thanh Nguyen—so my practice is naturally interdisciplinary and I don’t think about the work I do as an artist, a researcher, or what you might call an activist, as being separate.

I do feel a certain sense of responsibility having worked with different groups of vulnerable communities. As a former refugee, I understand vulnerability and victimhood. At the same time, I think it is important to recognise the agency of those being called victims. It’s true that refugees, as we understand them, are victims of certain geopolitical conditions or conflicts, and that might push them to make certain decisions that no one would want to make. Making a decision of leaving their home to seek refuge elsewhere, carrying out that plan, and escaping, takes a lot of courage. Some would spend years in detention centres learning new skills, new languages, organising or mobilising—those, too, take a lot of courage. As such, I would challenge people to consider refugees in this light as well.

You’ve shown works from the project in various contexts and situations all around the world—from Art Basel Hong Kong, to museum exhibitions. I wanted to speak to the way these histories are understood or transmitted across these contexts. In America, for example, narratives about the Vietnam War are often centered around American perspectives and involvement. This differs to how the Vietnam War is grappled with in the context of Southeast Asia. Having shown your work extensively both within the region and in the US, have you observed slight differences or nuances to the way in which your works are received and situated between these places?

These projects usually generate several outcomes. One outcome may happen within the refugee communities themselves as they feel empowered to reclaim the narrative, for example. Another outcome emerges from the various publics that encounter the works—certain awareness and new perspective—which the artists themselves also gain. Through the Hong Kong chapter of The Vietnam Exodus Project, some of the refugees I’ve connected with are stateless. Among these stateless Hong Kong residents, there is a group of homeless Vietnamese—the leftover refugees from the last century that were rejected by Western countries for their prior involvement with crimes in Hong Kong. The interactions and conversations I have had with these refugees really shaped the angle of my work. There’s a vast amount of literature that has been published about Vietnamese refugees. At the same time, this narrative is often shaped by someone else but not the refugees, at least in the public domain. I’m aware that some scholars have tried to work with oral histories and narratives as well, and there are a few published memoirs written by the former refugees. But these are few and far in between. When I first set out to do The Vietnam Exodus Project, I naively thought I could chronicle this huge history, but it’d be a daunting task for an artist-researcher. Being with the former refugees in Hong Kong has shed light on the purpose of the project. You can’t go back to fix the past and this project isn’t about coming up with a definitive historical record of what ‘truly’ happened. It’s about reclaiming the narrative and hoping to change things for current and future refugees. Coming to that realisation has given me a very clear objective for the project, which has since been focussing on the refugee experience and asylum policy.

In terms of the war in Vietnam, it has always been shaped in America with an American perspective for the American public, and its history has always been told from that perspective. In Vietnam, if your side loses the war, you don’t really get to tell your version of history or what happened in your experience. To me, it’s not so much about ideology or politics of the Cold War. It’s about ordinary people sharing their own histories as how they remember it. It’s so important to reclaim the narrative—not because our memories are more important than others, but because they are equally as important.

In an essay about the contemporary art scene in Vietnam, Viêt Lê draws a parallel between the maps you make and the dispersal patterns of fungal spores. Reading that recalled, for me, an earlier work of yours that’s also in the Singapore Art Museum’s collection, Enokiberry Tree in Wonderland. On that note, regarding the limitations of mapmaking and cartography, what do you make of alternative and perhaps more peripatetic modes (such as fungal networks) of charting space?

When I started working on those maps in relation to urban development in Saigon, I referred to them as fungi kingdoms. I saw how urbanisation was spreading through Saigon and it seemed to me like an organism without roots, living off other organisms. A lot of the dots and motifs I use in my maps reference bacteria and microorganisms, which I studied from an illustrative book. However, I see and think about things a little differently now. Although these developments seem to spread like fungi, the history of Vietnam provides a lot of context and precedent for it, as I’ve mentioned earlier.

Over the course of this conversation, we’ve been talking about space and how it can be both flattened and expanded. Flattened and condensed space, in particular, is something that we’re all feeling very keenly with this pandemic and the need to shelter in space. During this time, what are some of the things you have been thinking about, experimenting with, or working on?

I’ve been given a lot more time and space to reflect on the work that I have done over the past two decades in writing. It’s a very important exercise that I’ve taken on. I’ve also been thinking about how we can shift our practice. I think of myself as a rather practical person. I am not discounting the contribution of museums, institutions, and galleries to artistic ecosystems. We all work with one another to survive. However, when things fall apart, the centre cannot hold. Seeing the collapse of systems last year really made me think about ways in which artists could shift their practices. One of the shifts for me is conceiving and carrying out an academic alternative program called AGENCY | URGENCY: Learning with the Global South at the University of California, Santa Barbara. When everything is flattened into the two-dimensional space of a Zoom screen, our world can also be expanded. We could bring together speakers and participants from different continents to speak about their work and share their practice with the students. Through these online sessions, we were able to learn together and feel less isolated. Additionally, I’ve just been named a Mellon fellow at the Yale Center for the Study of Race, Indigeneity, and Transnational Migration for Fall 2021. Although art-making continues to centre my practice, shifting it a bit towards academia enables artists like myself to keep our work going, during this time.

Tiffany Chung (b. 1969) is a multimedia artist whose interdisciplinary and research-based practice unpacks spatial transformation, geopolitical partitioning, conflict, environmental crisis, forced displacement and refugee migration. Through her research, her works excavate traumatised topographies and their layered histories.

Joella Kiu is Assistant Curator at the Singapore Art Museum.