Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook’s Two Planets: Can Works of Art Exist Outside of the Museum?

01 Sep 2022

I have always wondered if artistic legacies – be it in the material form as artworks and objects, or in the immaterial form as creative practices – are worth keeping alive, and what it means to keep them alive. For me, a work of art is only considered alive when we are able to interact with it, as well as draw connections between the world it embodies and the one we live in. However, many of these works are now situated and presented inside some form of a controlled environment, with the most common one being a museum. Thus, I am most interested in exploring and imagining ways in which they could exist in meaningful ways outside of these traditional contexts.

In these contexts, there are inevitably going to be physical restrictions, which in turn rob audiences of a more intimate viewing experience. In some instances, museums could enact limitations as extreme as barring visitors from being in the same room as the work of art, unless they are being led on a tour. I once encountered this scenario when I visited the Neues Museum in Berlin to see the painted bust of Nefertiti. Having always been fascinated by Ancient Egypt, I was more than excited to see this beautifully preserved bust painted with vibrant colours. When reading literature about it online, it is said that when it comes to this bust, all “description is useless, [and that it] must be seen.” It was thus with bubbling anticipation that I arrived at the museum, only to realise that given the fragile state of the bust, general visitors could only admire it from adjacent rooms. Instantly, there was this frustration, because I flew 12,395 km to visit this museum, only to be stopped a mere 5 m away from the bust. The frustration was quickly washed over by an overwhelming sense of waste, because I realised that most viewers would probably never have the chance to witness the intricate details of this sacred artefact up close.

The imposed distancing could have been slightly redeemed if viewers were given the flexibility and freedom to linger in the adjacent rooms as we tried to get a better look of the bust. That was unfortunately not the case, as there were guards positioned at all of the entrance ways, ushering visitors to move along, once they managed to capture a photograph. If one would like to view the bust again, they would have to join the queue and wait for their turn, once more. In my opinion, the entire viewing experience was not only hurried and clinical, but also heavily disrupted. I began to question if there was a need for me to even see this work in-person, given that viewing conditions were that controlled, and why this work was even displayed in the first place. I left this particular exhibit with a slew of sentiments, of which most were negative.

For me, I believe audience perception and engagement are crucial in keeping artistic legacies alive, in a way where they could still prompt conversations and new thoughts. While these works of art have been, and are, key in the charting of history, I am curious to find out how the common man could relate to these works, and what purpose these works could serve for them. Is it respite? Is it distraction? Armed with these questions, I approached SAM’s Collection with apprehension and excitement. I was afraid that I would encounter more fragile works of art like the bust in the Neues Museum, but eager to also examine the acquisitions of a contemporary art museum. Eventually, I managed to locate a handful of works that harnessed artistic legacies.

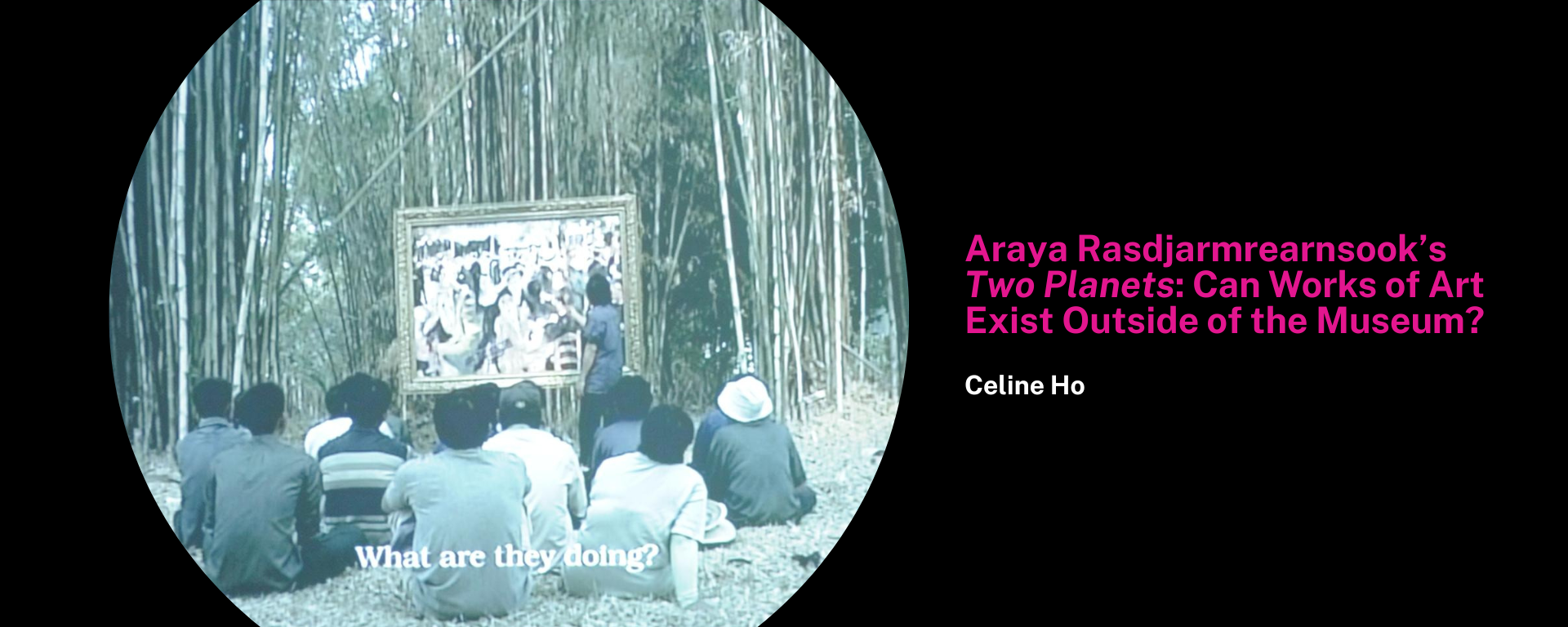

At one broad glance, these works appear to engage artistic legacies in a multitude of ways – some reference the composition or subject matter of notable works of art, while others appear to be inspired by well-known works in other artistic disciplines such as literature and architecture. From this set of works, I found myself most drawn to Two Planets by Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook, specifically to her art-making process and subject matter of this work. Here, she has brought life-sized reproductions of Western masterpieces that were painted in the 19th century to several rural villages in Thailand. Although the original masterpieces were all painted by esteemed artists such as Édouard Manet, Vincent Van Gogh, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Jean-François Millet, Rasdjarmrearnsook chooses to force them deep into the background and instead places the spotlight on the Thai villagers. Spontaneous, humourous and many a time politically incorrect, the villagers are unafraid of voicing out and coming forth to point out what they see in the artworks, and it is clear that they are enjoying the process. Through four separate viewing experiences, this work illustrates various refreshing perspectives through which these masterpieces could be interpreted and related to.

From the outset, Two Planets already shows signs of being the antithesis of the painted bust of Nefertiti in terms of being more physically accessible to its viewers. In Two Planets, the artworks are not only placed outside of the usual context of a museum, but are brought directly to their intended audiences. They are situated in the open and are thus vulnerable to the forces of nature. This is only possible because Rasdjarmrearnsook has chosen to work with images, or copies, of the masterpieces instead of the actual works, which allows her to successfully bypass all conservation concerns that kept the bust in “captivity.” As these copies have only visual, and not monetary value, they do not require extensive protection as the bust does.

Within this series of videos, the villagers are encouraged to speak their mind about the paintings, and to substantiate their statements with artwork details. As these villagers are likely to not have received any formal education in art, or even any tertiary education at all, their commentary is at times problematic, as sexist and racist remarks are made. When presented with Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass, a villager comments that the female subject’s breast is sagging because “she’s not lying down as she should.” When Van Gogh’s Noon: Rest from Work, after Jean-Francois Millet was shown, another villager then makes the assumption that the resting subjects are Arabs or “A-lab[s]”, since “they only lab (sleep).” Given the embedded prejudice in the villagers’ commentary, I initially wondered if there was any productive value in examining these conversations.

However, as the conversations progress, they start to take an interesting turn as the villagers begin to interpret the artworks on their own terms. We see them recalling and making references to local places such as the Buatong Waterfall and the village barn, as well as other local activities, including the Ram-Wong, a traditional folk dance, and an intra-village sporting event. When commenting on Van Gogh’s Noon: Rest from Work, they use their contextual knowledge about agriculture to rationalise how the labourers must have used “lemongrass leaves to tie the bundles [of hay],” just because they too use lemongrass leaves for tying purposes. While the artworks are seemingly reduced to mere tools for the facilitation of conversations, it is also in these circumstances that they are the most alive to me, for the way they are able to prompt such personal and refreshing responses. By relating what they see to their day-to-day life, the villagers are able to bridge the gap between what is pictorially depicted and their own reality. Although they did not understand the canonical significance of these “masterpieces,” they still managed to engage in some form of discourse by drawing on what they knew best. In such moments, the villagers and their opinions become the subject matter as we, the secondary viewers, glean insights into their world.

Looking at the settings in these videos, there is too, an air of innocence. At a quick glance, the villagers resemble a group of students on a field trip. While Rasdjarmrearnsook can occasionally be heard asking guiding questions, the conversations are almost always flowing. Although the villagers may not resemble the typical museum-goer in terms of educational background, dressing and demeanour, it is difficult to disregard the fact that they are truly engaged in the process, and that they are still viewing art and making sense of what they are seeing. Seeing how these villagers add on to one another’s comments, I begin to wonder if the most ideal space to view art is indeed the traditional museum or gallery, where there is hardly any allowance to create any commotion without disrupting others.

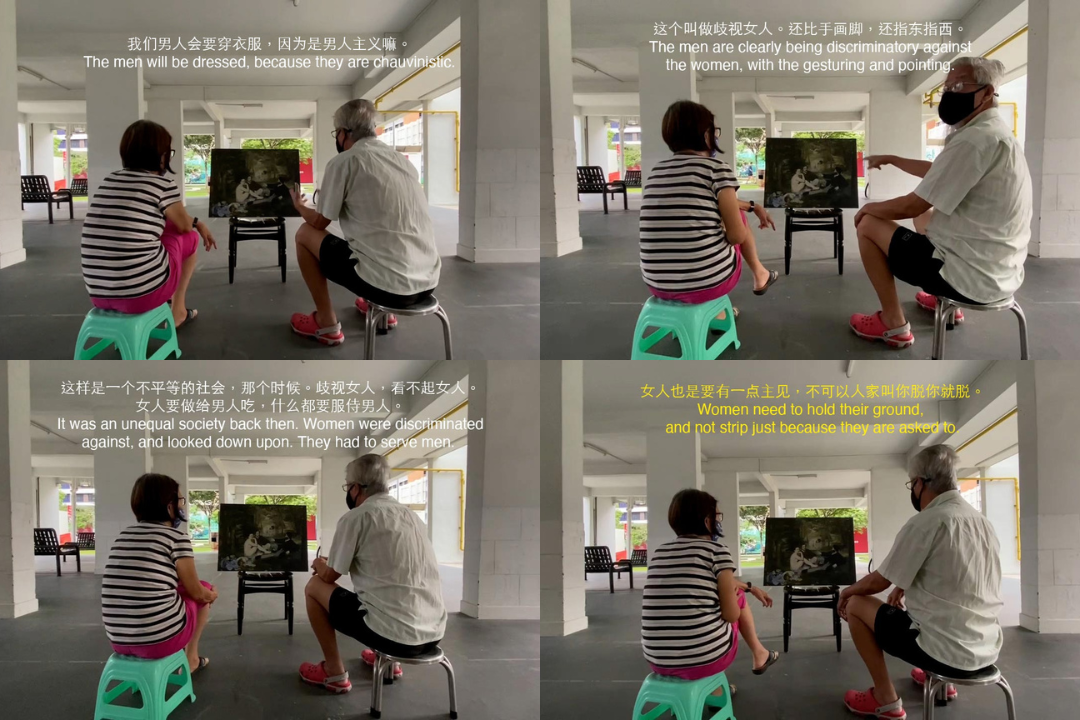

Bearing this particular thought in mind, I started to envision creating a space for similar conversations with the people around me, so as to examine the effects of bringing a “masterpiece” out of a controlled environment, and to the masses. While I was undoubtedly captivated by the conversations facilitated by Rasdjarmrearnsook, and inspired by the potential of such conversations to surface preconceived notions and deeply entrenched values, I felt that it was important for me to recreate Two Planets. The original work is set in rural Thailand, and therefore there is still a sense of distance between the work and myself. For my own experiment, I situated a copy of Édouard Manet’s The Luncheon on the Grass in the middle of the void deck, and the participants were my grandparents.

Here, I have chosen this particular artwork for its rich commentary on gender norms, specifically the reverting of the male gaze. Although the female subject in the foreground is completely naked beside two fully clothed men, she is looking directly at the viewers, thus establishing the fact that she is not just the object of lustful viewing, but a viewer too. While I understood that my grandparents might not be able to pick up these nuances, I thought that this notion of gender dynamics might be an easier entry point for them, and thus picked this work over the other three masterpieces that are also featured in Two Planets.

In this experiment, although my grandparents point out similar details as the Thai villagers, the tone of these two conversations is largely different. Whenever the villagers – both male and female – make sexist attacks on the nude female subject, these comments are often met with roaring laughter from the rest of the crowd. They appear to revel in their assumption that the said subject is promiscuous. On the other hand, my grandparents did not seem fazed by the nakedness, although they were viewing the image in the open where their neighbours could see them. Instead of focussing on the fact that the subject is naked, they quickly delve into some form of social commentary where they discuss the power relations between the two genders. While my grandparents also make assumptions in their viewing process, they give the subjects, especially the nude female subject, a benefit of doubt; some sort of blind faith that these subjects were acting within the social norms at that point in time rather than out of their own will. My grandmother, whose comments are in yellow, also notes that times have changed, and women now need to hold their own ground.

Just like how we catch a glimpse into the villagers’ life through their commentary, I have gleaned insights of the world my grandparents live in, as well as of their relationship. Although they are both aligned on the fact that the image depicts a time and space where gender dynamics are imbalanced, they seem to have internalised these norms too. Throughout the 18-minute-long experiment, my grandfather can be seen leading and holding the conversation, while my grandmother mostly sits and observes silently. At times, he asks for her thoughts, tells her how she should feel and act, and even prompts her to agree with him. And she does. Although this has been their way of coexistence that I have come to know and accept, it was in that moment when I sat behind the camera that I realised perhaps the world they live in is not that different from the one Manet depicted.

Besides my grandparents’ commentary, the most enjoyable aspect of this experiment for me was the interactions we shared with the rest of the community. While the conversations in Two Planets are held in various idyllic settings, my experiment was carried out in a state of flux as residents could be seen always entering and exiting the frame. Towards the end of the experiment, a family friend who coincidentally walked by, came close to get a better glimpse of the image, and this also encouraged other passers-by to slow down and approach us. Although they did not comment on the image, it was apparent that it piqued their interest. As we basked in the presence of a situation that was out of the ordinary and spent some time together, I realised perhaps that this is how art could continue to live on.

Through the close examination of Two Planets and the facilitation of my own conversation, I have come to learn that the artistic masterpieces need not always be the main focus. In both contexts, these copies are merely visual aids that prompt for responses, and resources that provide evidence for their viewers to substantiate their comments. Although these masterpieces are clearly significant works of art, it is important to acknowledge that they were painted centuries ago, where artists were challenging and operating under a different set of ideals and thus were depicting a different world. When viewing these works in the present world, if without public discourse or collective exchange, viewers could only glimpse into the world depicted, but are likely to find difficulty in relating what they see to their own lives. By hearing what others have to say about the work and in turn contributing your own thoughts, or simply by watching a conversation unfold before your eyes, this is how the two worlds could start to collide and intermingle, thus allowing us to see new meaning. I believe this is an experience that would be refreshing even for those who are well-versed in art.

Celine Ho is an English Literature and Art History student at Nanyang Technological University (NTU). Her research interests include Southeast Asian art, as well as sites and modes of display. She was an intern at the Singapore Art Museum between May to September 2021.